A NEW ARCHITECTURAL APPROACH TO THE ALCAZABA AND THE TORRE DEL HOMENAJE

LA ALCAZABA Y LA TORRE DEL HOMENAJE BAJO UNA NUEVA MIRADA ARQUITECTÓNICA

Adelaida Martín Martín

Universidad de Granada

RESUMEN El presente artículo, es un fragmento de la tesis doctoral: «De la QASABAT al-QADiMA a la ALCAZABA ROJA», en la que se realiza un detallado estudio de la Alcazaba de la Alhambra, elaborado gracias a la recopilación y análisis de la diversa y amplia información existente sobre la misma. En este contexto abordamos una descripción del conjunto, y se elige la torre del Homenaje por ser un elemento clave en el funcionamiento de la Alcazaba, siendo la torre más importante desde el punto de vista estratégico. Se ofrece una descripción de la fortaleza y del elemento elegido, su evolución histórica y su caracterización arquitectónica, aportando inéditas planimetrías e infografías sobre la Alcazaba. Gracias a la documentación gráfica existente y tras numerosas visitas a la Alcazaba; para comprobar y tomar medidas in situ, hemos redibujado la Alcazaba y sus elementos para ser más fieles a la realidad material existente y mostrar con claridad una de las mejores alcazabas hispanomusulmanas.

PALABRAS CLAVE Alhambra; Alcazaba; Torre del Homenaje; Construcción defensiva; Modelado 3D

ABSTRACT The following article is part of the doctoral thesis entitled “De la QASABAT al-QADiMA a la ALCAZABA ROJA”, a detailed research into the Alcazaba of the Alhambra, drawing from a wide range of diverse existing literature. In this context, a general description of the fortification is presented and, for that purpose, the Torre del Homenaje is selected since it was a key element in the Alcazaba’s functions and also, as it was the most important tower from a strategic point of view. A description of the fortress and its key tower is provided, together with a historical evolution and architectural characteristics, including unpublished renderings of the Alcazaba. By means of the existing graphic visual information and after the numerous visits to the monument, the Alcazaba and its elements have been redrawn to create a more precise representation of the exiting material, and to clearly portray one of the finest examples of Hispano-Muslim Alcazabas.

KEY WORDS Alhambra; Alcazaba; Torre del Homenaje; Defensive Construction; 3D Model

Cómo citar / How to cite MARTÍN MARTÍN, A. A new architectural approach to the Alcazaba and the Torre del Homenaje. Cuadernos de la Alhambra. 2019, 48, 175-199. eISSN 2695-379X.

INTRODUCTION

Most texts referring to the Alhambra have typically focused on the study of the palaces due to their impressive architecture and dazzling beauty. The Alcazaba has usually been left aside or, in the best case, it has been treated in a descriptive way and thus its worth as one of the best citadels in Spain has been overlooked. Only a few authors, such as Manuel Gómez Moreno, Leopoldo Torres Balbás, Jesús Bermúdez Pareja and, more recently, Basilio Pavón Maldonado, Antonio Malpica Cuello, and Carlos Vílchez Vílchez, among others, have provided in-depth studies on the subject and bestowed on the Alcazaba the significance that it deserves.

There are two main reasons to carry out exhaustive research on the Alcazaba of the Alhambra. The first one is that it is a sample of defensive construction that became a model for other Hispano-Muslim fortresses, and the second one is, as mentioned, that it is a building that has long stood in the shadows of the beautiful palaces of the rest of the citadel, which often have disguised its value and this in spite of being the seeds and origin of the entire complex.

Until the beginning of the 19th century, the Alcazaba was just one of the many obliterated and forsaken buildings in the Alhambra, a state of dereliction that could be seen in the ruined towers and walls, neglected vegetation and general lack of maintenance. At the end of that century, however, thanks to a series of finds, mostly by Mariano Contreras, Modesto Cendoya, Torres Balbás and Bemúdez Pareja, the space became the subject of a series of interventions that mainly involved the cleaning of rubble and riddance of elements lacking in value 1. The removal of rubble from the parade ground, which up until then had been a sort of untended vegetable garden and orchard, meant the discovery of the military quarters, attracting the attention of the first researchers, who had previously seemed more interested in the ornamentation of the palaces than in the archaeological remains found in their surroundings.

In this article, we approach the Alcazaba of the Alhambra in order to recognize its fundamental value as a model of defensive construction that adapted to its environment and took advantage of it whenever it was necessary to implement reforms and modifications.

The Alcazaba is described in detail, and the Torre del Homenaje has been chosen as an example of the work that has been carried out throughout the doctoral thesis regarding each of the components of the Alcazaba. A graphic description of the extant elements, a definition of their physical and spatial characteristics, and a study of the period when each of them was built and of the transformations that they suffered through time are included.

Obviously, it is very complicated to establish a fully-documented chronology. The significant lack of written sources, unreliable plans and the scarcity of archaeological data prevents us from understanding clearly and concisely the way in which the premises were originally designed and how they materialized through time. By way of a conclusion, in this paper plans and renderings accompany the literary description of the building in the hope that they will help to understand the complex of Alcazaba visually as well as each of its composing elements. This task was carried out by gathering the abundant and varied graphic information that exists and by correcting the errors and inconsistencies that it presents to the extent possible.

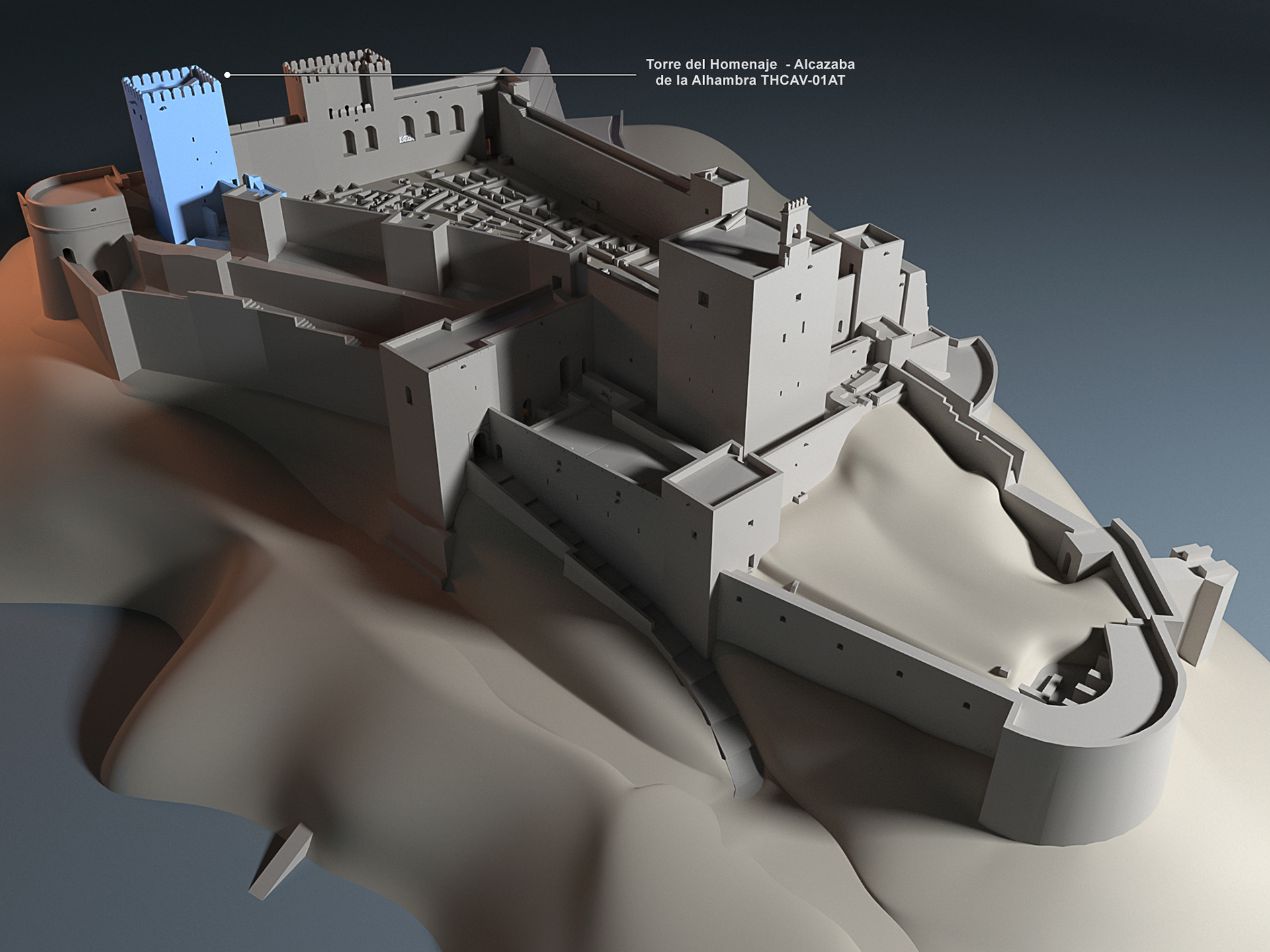

Under our guidance and using all the available information, the design studio Carlos Álvarez Velázquez built from scratch a 3D model of the citadel that can be visualized at https://youtu.be/Fhj219-YTHs.

In the course of our research we constantly faced problems regarding the inconclusiveness of partial studies which, given their mostly descriptive nature, had no technical character. As mentioned, the lack of archaeological information and the poor quality and incongruity of the plans hindered the investigation.

During the data collection process, the Alcazaba itself was used as the main source. The value of archaeological research to contribute to the historical knowledge of the past was taken into account, as well as the existing historical documentation that was considered useful to establish possible dates and all the previous research work that, to some extent, focused on the evolution of the Alcazaba. Numerous images were analyzed and interpreted through the lens of their historical and cultural context, considering this most intuitive way to get to know the Alcazaba and its transformations. Each image of the Alcazaba of the Alhambra contains an interpretation of its evolution, offering a story or memory of the complex’s life throughout time.

Lastly, the most relevant materials and building techniques that were used in the Alcazaba, whether habitual or exceptional, were also studied, together with the constructive typologies and their historical evolution, in order to establish a chronology.

By using such a methodology and proposing such objectives, we present a fragment of the doctoral thesis “De la QASABAT al-QADIMA a la ALCAZABA ROJA”, in which an in-depth study of one of the best citadels in Spain is offered.

THE SETTLEMENT ON THE SABIKA HILL

In this section we tackle the building activity that could have taken place on the Sabika hill up to the time of the arrival of the Catholic Monarchs, starting with the period in which it is thought that the Ibero-Roman Granada (Iliberri) was first settled.

Authors such as Leopoldo Torres Balbás 2 and JesúsBermúdezPareja 3 are of the opinion that the Alcazaba was formalized after the re-construction of an existing late-Roman castle on the Sabika, the name the hill of the Alhambra receives. Their claim is substantiated by the fact that the foundations for most of the walls and some of the towers can be dated back to a period before the 11th century.

However, other scholars, like Antonio Malpica Cuello, contend that it is rather complicated to determine in all certainty when the Sabika hill was first settled:

[…] the traces remaining today do not permit to know vestiges pertaining to those possible first constructions and, in any case, they should not be considered more than a military structure clearly differentiated from the city par excellence in that space, Ilibra . . . thus , today it is accepted that […] the Red Hill was first occupied in medieval times. 4

It is not illogical to think that the vestiges pertaining to this period can come from materials that were originally used in the Roman city of Iliberri due to the fact that, upon their arrival, and because of the lack of materials and haste, the Arabs may have used such material to erect their first buildings. That possible reuse of materials may have favored the different theories regarding the dates of occupation of the Sabika hill.

Following that line of thought, even Leopoldo Torres states at some point that both the Roman graves found on the southern slope towards the Mártires and the architectural fragments and inscribed stones from that period that were found throughout the grounds, walls and towers of the Alhambra could have been taken there from the Qadima Alcazaba hill across the way, where similar remains were discovered in the 17th century 5 after some excavations.

In his opinion, the same thing may have happened with regards to the Visigoth stone plaque that was unearthed in the Casa Real Vieja during the second half of the 16th century and that could have been brought there from another site. 6

Therefore, since there is no reliable documentation on the subject, the time when the Sabika was first settled is yet to be determined. The most recent research suggests that it must have been after the Roman and Visigoth periods, thus it is difficult to establish an origin of the building before the 9th.

9TH CENTURY. HISN OR QAL’A AL-HAMRA

The earliest written documents pertaining to the site that is the object of our analysis come precisely from the 9th century. The oldest reference dates from the year 860, and it states that there was a castle on the site of the Alcazaba where Muslim troops took refuge whenever they were harassed by Andalusian natives. A similar account appears in sources by Muslim historians describing events that took place in the year 889: Arabs under the leadership of Sawwar who were fighting Andalusian natives found shelter in the castle, which is now called Qal’a al-Hamra, or “red castle”. 7

Those first references must be taken with caution due to the propensity of Islamic historiography to offer subjective interpretations of news. There are versions that adapt to contemporary events by using the names of well-known places and people 8. In addition, the analyzed texts are not originals but later copies of them, which adds even greater uncertainty.

The first historic references to Qal’a al-Hamra as an occupied location appear in the following texts:

In Ibn al-Jatib’s Al-Ihata (14th century):

[...] he was the one who fortified Madinat al-Hamra during the night, so that the light of the fires could be seen by the Arabs of al-Fahs [vega]. 9

In a text by historian Ibn-Hayyan (11thcentury) describing the Muladí uprising:

Intense nationalistic feelings started to grow among the Arabs and Christians of the city of Elvira and divided them into two antagonistic sides. The Arabs, being a minority there, had to resort to the Granada fortress (Alhambra) as their refuge even though its walls were in ruins at that time. They took shelter there and, during the day, began to fend off the attacks of the Spaniards and Muladís, their bitter enemies, who harassed them and forced them to fight. At night, by the light of their torches, they rebuilt the damaged sections of the fortress. 10

The existence of a fortress is made clear by both texts and two possibilities arise:

- That a castle existed in Garnata which was restored by Sawwar Ibn Hamdun in the 9th century.

- That Sawwar himself built a fortress in the 9th century.

At present, both options are hard to confirm and demonstrate because no systematic archaeological studies have been carried out in this section of the Alhambra 11 and the standing structures of the Alcazaba do not permit us to recognize vestiges of those first constructions.

Regarding the origin of the name al-Hamra, which appears in the 14th century text, there are several theories:

- The reddish light of the torches that were used to work at night gave name to the site.

- The name comes from the reddish color of the ground of the hill itself.

For the majority of the authors studied, the name comes from the color of the clay of the hill where the monument is located, which was used both to build its foundations and walls.

A more recent study by María José de la Torre yields objective data in relation to the original color of the external walls of the Alhambra. She dates the origin of the monument in the 11th century. 12

Independently from these theories, it is clear that the name of the Alhambra, al-Hamra, is previous to the rise to power of the Nasrid dynasty and that the fortress appears under such a name in the texts that were analyzed.

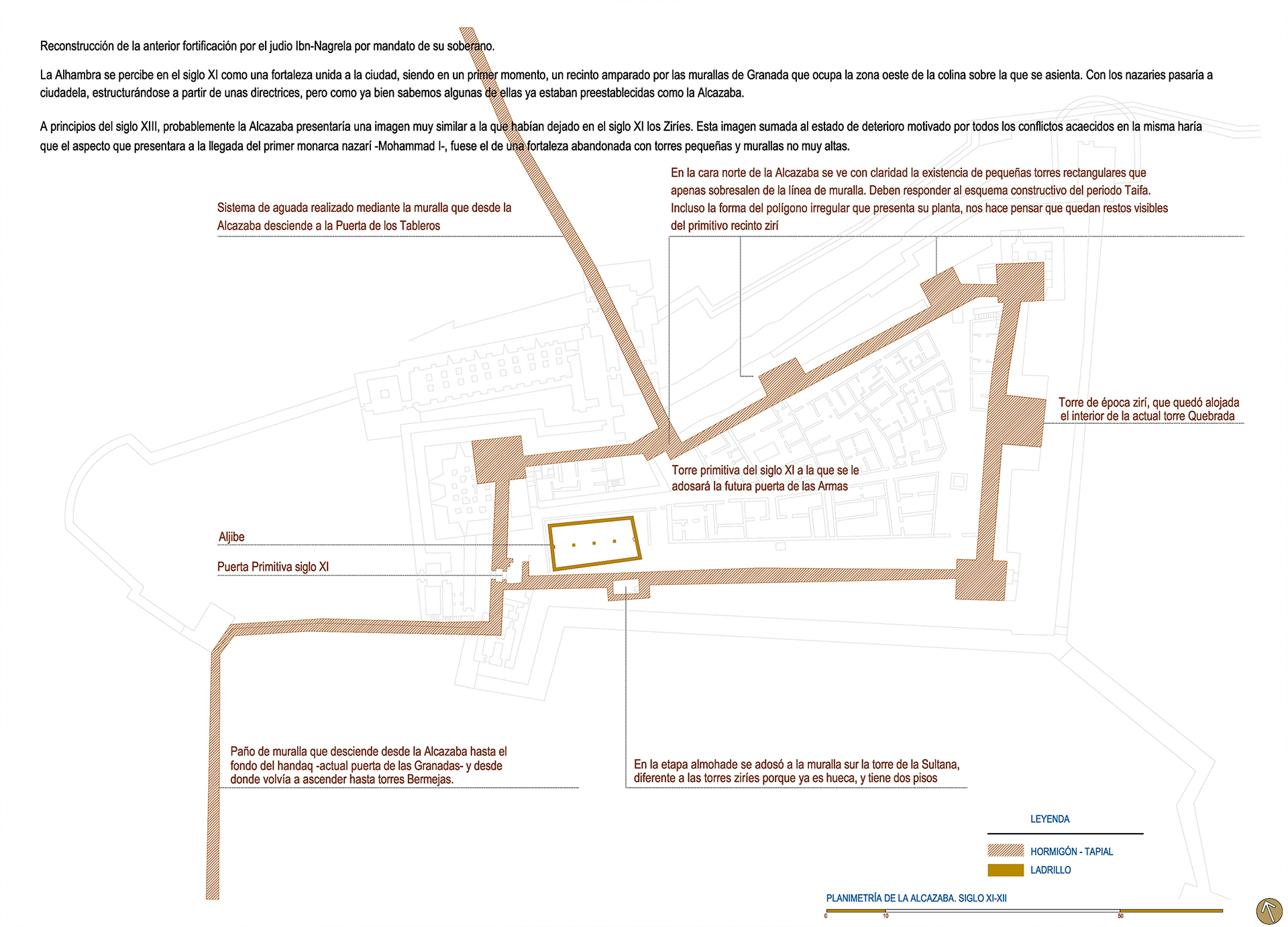

11th CENTURY. ZIRID PERIOD.

HISN AL-HAMRA

For the analysis of the history of the monument in the 11th century, researchers rely on the memoirs of Abd Allah (1077-1090), which offer new data on the historic evolution of the Alcazaba of the Alhambra. The texts mention several constructions on the Sabika hill during that century.

According to this source, one of those constructions was the fortress “Hisn al-Hamra”, built by the Jew Yusuf Samuel Ibn Nagralla (an advisor to the Zirid monarchs around 1052) as a refuge for his family and himself:

In his memoirs, Abd Allah, the last granadino Zirid, says that the Jew Samuel ibn al-Nagrila [. . .] had the Alhambra fortress built to take refuge in it with his family until peace be restored upon the arrival in Granada of king al-Mu’tasim of Almería and his taking control of the city. Therefore, the construction of the red fortress must have taken place in 1052, the year when al-Mu’tasim began to rule over Almería and the years 1056-1057, the time when the well-known vizier was murdered. 13

We must point out that the 11th century was characterized by the existence of continuous conflicts among Christians, Jews and Arabs. In the mentioned memoirs, the construction by Samuel ibn-Nagrela of a fortress on the Sabika that became his residence is seen, in this context, as a sign of the Jew’s fear of a revolt of the Muslim population against him. Leopoldo Torres Balbás interprets that Abd Allah refers to the re-construction extension of a previous fort.

As for the settlements on the hill, the Arab texts state that after the tragic death of Joseph ben Nagrela, Abd Allah himself says that when he ordered the construction of a wall contiguous to the Alhambra, the workers found a pot full of gold coins while digging on the site of the Jew Abu-l-Rabi’s house, Joseph’s uncle:

These gold yafari coins had been issued by the taifa king from Zaragoza, Abu Yafar Ahmad ibn Sulayman, whose kunya gave name to the Aljafería. Since these foundations of the new wall formerly had been part of the house of the Jew Abu l-Rabi, King Badis’ treasurer, Abd Allah thought that there may be more buried treasures, and he ordered his son to come. The latter lived in Lucena, where he had fled from Granada because of the “pogrom” of 1066. He was the son-in-law of Ibn Maymun, a trustee of the Lucena Jewish community who had been named by Abd Allah himself. Ibn Maymum thought that the summon was part of a plot to have his son-in-law sent to prison, so he advised him not to go. In addition, as a result of all this, Lucena’s Jewish population rose up in rebellion. 14

The section of wall that is mentioned in the text is the one that descends from the northern side of the Alcazaba and connects with the city through the Bab al Difaf gate. It was excavated and rebuilt using brickwork in 1960 by Jesús Bermúdez Pareja.

From these texts it can be deduced that the Alcazaba was part of the settlement of Granada in the 11th century. On this subject, Antonio Malpica Cuello says:

The Alhambra [was consolidated] as a citadel that was connected to the city by a section of wall and a coracha that made it possible to get water from the Darro . . . On the north side of the Alcazaba some small towers that barely break the line of the wall can be clearly distinguished. They must be the result of the building design from the Taifa period. Even the irregular polygonal shape of their plan makes us think that visible traces of the primitive Zirid enclosure must still remain […] The second text stresses that when the wall that connected the Alcazaba to the city was built, some remains, possibly from the Jewish vizier’s construction, were discovered […] Anyhow, it is obvious that the consolidation of Granada as an urban center and its growth put into play the land on the Red Hill, giving it a predominantly military role. The adaptations carried out are perceptible without a great deal of difficulty by observing the standing remains, even though a detailed study is needed. The most relevant of those reforms is the reuse of the wall to build a coracha that went down to the Darro from which to take water. There are still some visible vestiges of this at the so-called Puente del Cadí, which is really Bab al-Difaf. 15

The analyzed texts prove that:

- The Alhambra citadel was designed, like the city of Granada, taking into account the functional and spatial transformations that the fortification underwent through time. It went from being a Hisn (in the 11th century) to being a Qasabat (in the 13th century) to later become a Madinat.

- In the 11th century, in the Alhambra area there were homes belonging to Jews of high social class.

- The fort of the Sabika was incorporated into the walls that surrounded Granada during the 11th century by means of a coracha system and the Puerta de los Tableros(Bab al-Difaf).

Other texts addressed in the memoirs mention possible improvements to the Hisn al-Hamra by describing the way in which Abd Allah rushed to implement in the Granada fortifications the defensive improvements that were observed in the Bellillos fortress, which had been built by a contingent of Alfonso VI’s soldiers at the service of King Al-Mu’tamid of Seville and taken by the troops of the king of Granada in 1075. 16

Regardless of this, it is very difficult to know what happened between the 11th-century events mentioned above and those that Abd Allah describes in his memoirs, in the case of the previous existence of a fortress on the hill.

DESCRIPTION OF THE PREMISES

IN THE 11th CENTURY. HISN AL-HAMRA

The Hisn al-Hamra is located on the Sabika hill, which overlooks Granada as a true vantage point that controls the entire territory and provides the appropriate setting for the kind of defensive system that characterized the cities of its time. In addition, the topography of the site and easy access to the water of the Darro River, a must for the urban development of the area, allowed it to evolve towards a citadel.

The Hisn rose on the westernmost end of the hill and adapted to the relief of the site very much in the same way the Hisn Garnata did on the adjacent hill. 17 The fortress presented an irregular shape, with longer sides to North and South, and shorter sides to the East and West. the eastern side being the longest of the two. The entrance was located at the southwestern end of the enclosure.

In my opinion, in ben Alhamar’s Alcazaba in Granada, the walls with base slabs and the small towers that barely show on the north wall, together with the massive dry-stone ashlars of some sections could be re-used vestiges from the 11th and 12th centuries and should be studied as pre-Nasrid architectural elements [...]The irregular shape of the fortress also favors the idea that the fortress is a pre-Nasrid construction although, like in other 11th-century fortresses, its layout may respond to the abrupt nature of the terrain. 18

During this period, the north side was reinforced by means of three towers, as the construction system used, rammed earth with lime, and the size and proportion of the reinforcements show.

Of the pre-Nasrid Muslim Alhambra, the constructions of which I have tried to trace through the sparse historical accounts, there are only a few remnants, such as some foundations and small sections of walls and towers belonging to the fortification works on the east and north sides of the 13th-century Alcazaba. They were built with very hard mortar that incorporated rounded stones. On the corners of the towers, stone slabs alternate with double rows of thick bricks, which are also used in the walls. 19

There were no towers on the south side until the 12th century, the Tower of the Sultana being built during the Almohad period.

The eastern side was reinforced with three towers that are later incorporated into other bigger towers. Such is the case of the central tower, enclosed by the Torre Quebrada at the time of Yusuf I. Other towers were replaced. The towers at the ends, for example, were substituted by new towers, like the Torre del Homenaje or the Torre del Adarguero during the reign of Muhammad I 20.

From this period, within the enclosure, are the water cistern and the parade grounds, where tents were set up 21. As for the water cistern, Gómez Moreno points out that people went down from the Alcazaba to get water from the river and then back up to fill the cistern and thus provide the fortress with water. Rain water was also stored in the cistern. There was no running water on the Sabika hill before the 13th century. 22

During that period, on the northwestern corner, there may have been another reinforcing corner tower, which was later replaced by the Torre de la Vela in the 13th century.

There are discrepancies with regards to the date of the primitive entrance into the enclosure 23. Our proposed date is the 11th century even though we admit that it was refurbished later (13th century) and that its construction was problematic. We must also conclude that archaeological studies on the subject can be very complicated due to:

- The great number of reforms that it underwent from the 11th to the 16th century, and

- The fact that all of those refurbishments present similar building techniques and construction processes, complicating attempts to date the different phases.

12th CENTURY. ALMOHAD-ALMORAVID PERIOD:

AL-QAL’A-AL-HAMRA

Historical documents show that during the 12th century the fortress was used as a refuge by the nationalist party against the Almoravids and Almohads, who held the Qadima Alcazaba across the hill. Upon taking the fortress, the Almohads encounter a ruinous after all the vicissitudes that it suffered during the nationalistic resistance.

Balbás points out that the fortress on the Sabika must have had greater strength and defensive capacity during this period due to the fact that the garrison was successfully defended while, by contrast, the Almohads and Almoravids took Granada easily and held their position both in 1145 and 1162. 24

The Torre de la Sultana was erected on the south wall of the Alcazaba during the Almohad period, between the 12th and 13th centuries. The tower differs completely from those previously built during the Zirid period, regarding both the building techniques that were used and its spatial characteristics. As a matter of fact, it is a hollow structure and has two storeys.

In short, we could say that there was no new building activity on the hill during the 12th century. At most, there were some repairs and adaptations when it was used as a refuge in the fights against the Almoravids in 1145 and the Almohads in 1162, when Granada was taken by the Andalusian forces of Ibn Hamusk, Ibn Mardanis’ son-in-law.

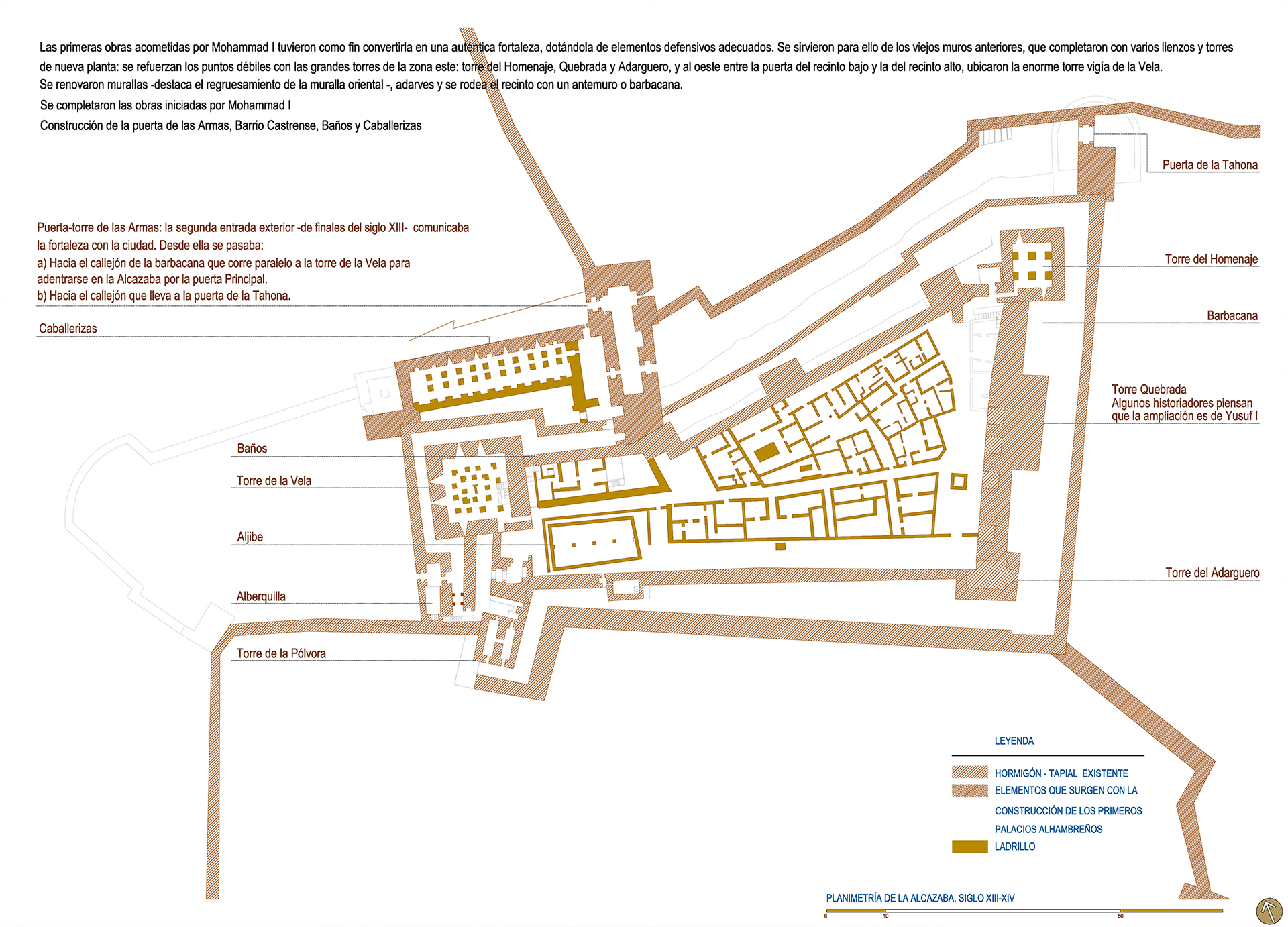

13th CENTURY. THE NAZRID PERIOD: AL-QASABA AL-HAMRA AND MADINAT AL-HAMRA

In the 13th century , in the year 1238, Muhammad Ibn al-Alhamar made Granada the capital city of the dynasty that he started, the Nasrids. At first, he established his residence in the Alcazaba Qadima, but a few months later he moved to the fortress on the Sabika, which offered a better strategic situation and thus was more appropriate to oversee the creation of the Alhambra citadel. He brought in water from the Darro and repaired the old fortress (Hisn) and the two corachas that joined it to the Albaicín and the Castle of Mauror.

Bringing running water to the hill was essential for the urban development of the citadel. Muhammad I had the Acequia Real or Acequia del Sultán (al-saquilla al-sultan)built to guarantee a permanent provision of water for the Sabika hill. Thus, in the 13th century, the settlement of Madinat al-Hamra was made possible. This was one of the first planning actions in the Alhambra and it ensured the development and prosperous growth of the hill.

Before the 13th century, there was no functioning hydraulic system to supply the buildings on the Sabika hill with water. From the 11th century to the 13th century the water supply was guaranteed by the use of the coracha that facilitated the carrying of water from the Darro to the water cistern in the Alcazaba. But for the cistern and the associated coracha, there is no archaeological evidence to point to the existence of a previous system of water conduction or similar infrastructures 25.

When the Nasrid dynasty settled in Granada, the Darro was still considered the most appropriate water source to supply the hill with abundant water, hence leading to the construction of the aforementioned Acequia (ditch).

Muhammad I began a building program on the Sabika which culminated in the establishment of a new medina juxtaposed to the Garnata medina in later dates.

Muhammad’s interventions took place between 1238 and 1239. After that, his son Muhammad II completed his work and undertook the task of starting new buildings outside the fortress on the eastern side of the hill 26. Muhammad I built above the foundations of some ruined towers and re-constructed existing sections of wall. His goal was to turn the building into a true fortress by providing it with appropriate defensive elements that adapted to the new needs 27. The existing walls were re-used and they were complemented with new sections and added towers. The weak points were reinforced with the large towers on the east side: the towers of the Homenaje, of the Adarguero and Quebrada. On the west the huge watchtower of the Vela was erected. Walls were reinforced (the widening of the eastern wall is worth mentioning) and the complex was surrounded with an outer wall or barbican. The walls were prolonged along the hill, enclosing the new palaces. The moat in front of the fortress—what is now known as the Plaza de los Aljibes—was maintained and access was made more difficult by including angled entrance gates. The topography of the Sabika made any change in the extension of the fortress impossible, which meant that any modification had to consist in an improvement on the existing defensive system. The great volume of the new towers within an area that could not be enlarged made the fortress look compact and impressive.

Some of the towers are of great size and represent true independent fortresses, which was an absolutely new conception in the context of the prevailing Andalusi military architecture. The most impressive of all those towers is the Torre del Homenaje. Its inner distribution, with three clearly-defined areas with independent accesses (storage facility/dungeon, garrison, audience room, residence), gives it a simultaneously military, administrative and residential character that until then was unknown in al-Andalus.

Besides the reinforcing and formalization of new wall sections, towers and gates, new bath facilities were built, as well as housing on the parade grounds. By means of these interventions, the lines for the new military profile of the Sabika hill were marked, and the Nasrid sultans that followed continued along these lines to complete the Alcazaba and the citadel that had been established under its protection. During the Nasrid period, after the reigns of Muhammad I and Muhammad II, some key elements were added to update the fortress: the tower-gate of the Armas to the north—possibly built by Muhammad III, the gate of the Tahona where the Alcazaba and the palaces met, the horse stables on the west side of the gate of the Armas, and the Torre Quebrada to the east, built during the time of Yusuf I to replace the previous, smaller Zirid tower.

With the planning of the urban development on the hill, the Nasrids built the tower-gate of the Armas in order to communicate the first Alhambra palaces with Granada, reinforce the northern end of the fortress and defend the first direct connection between Granada and the Alhambra. Therefore, this gate resulted from directly from the construction of the first Alhambra palaces, the construction of which is attributed to Muhammad II and Muhammad III. There are two hypotheses:

- The original gate was constructed by Muhammad II and replaced later on with another during the reigns of Isma’il or Yusuf I.

- The original gate was built by Muhammad III, the king who planned and defined the urban development of the Alhambra.

Both hypotheses are difficult to prove, and in order to reach a plausible conclusion, a comprehensive archaeological study of the area would have to be undertaken. In our opinion, the second option is more likely to be true.

Independently from those two possibilities, there are two architectural elements related to the gate that make no sense without the gate itself: the Puerta de la Tahona on the northeast angle of the Alcazaba, a hinge element between the Alcazaba and the “urban distribution” square (located in front of the Tahona door and the Alhambra palaces) and the horse stables, which were used to lodge the horses of those who rode in through this northern access.

IL. 1. Adelaida Martín Martín: Historical evolution of the Alcazaba (11th-12th centuries). 2015. Plan 2386x1717 pixels

IL. 2. Adelaida Martín Martín: Historical evolution of the Alcazaba (13th-14th centuries). 2015. Plan 2386x1717 pixels

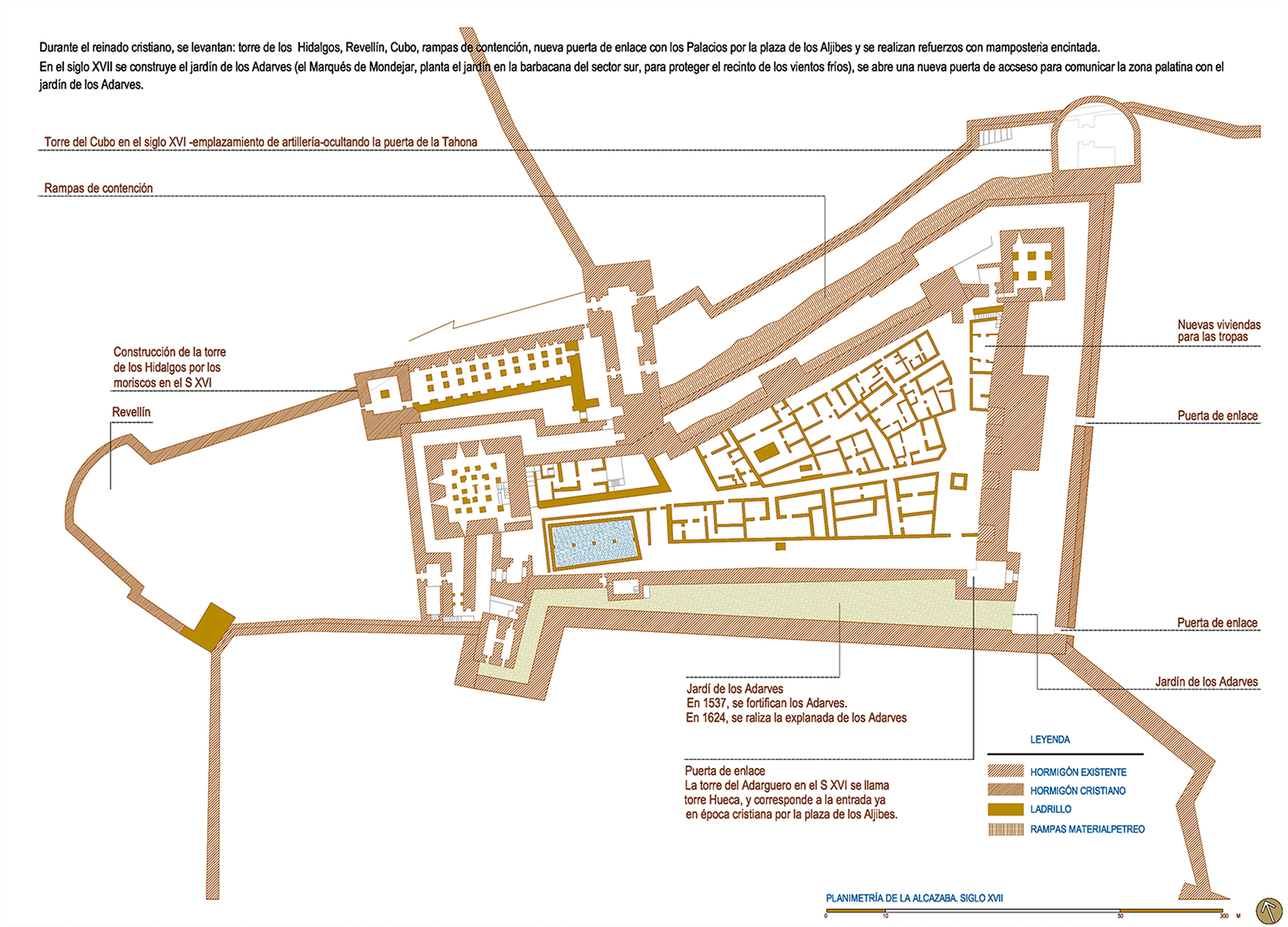

IL. 3. Adelaida Martín Martín: Historical evolution of the Alcazaba (17th century). 2015. Plan 2386x1717 pixels

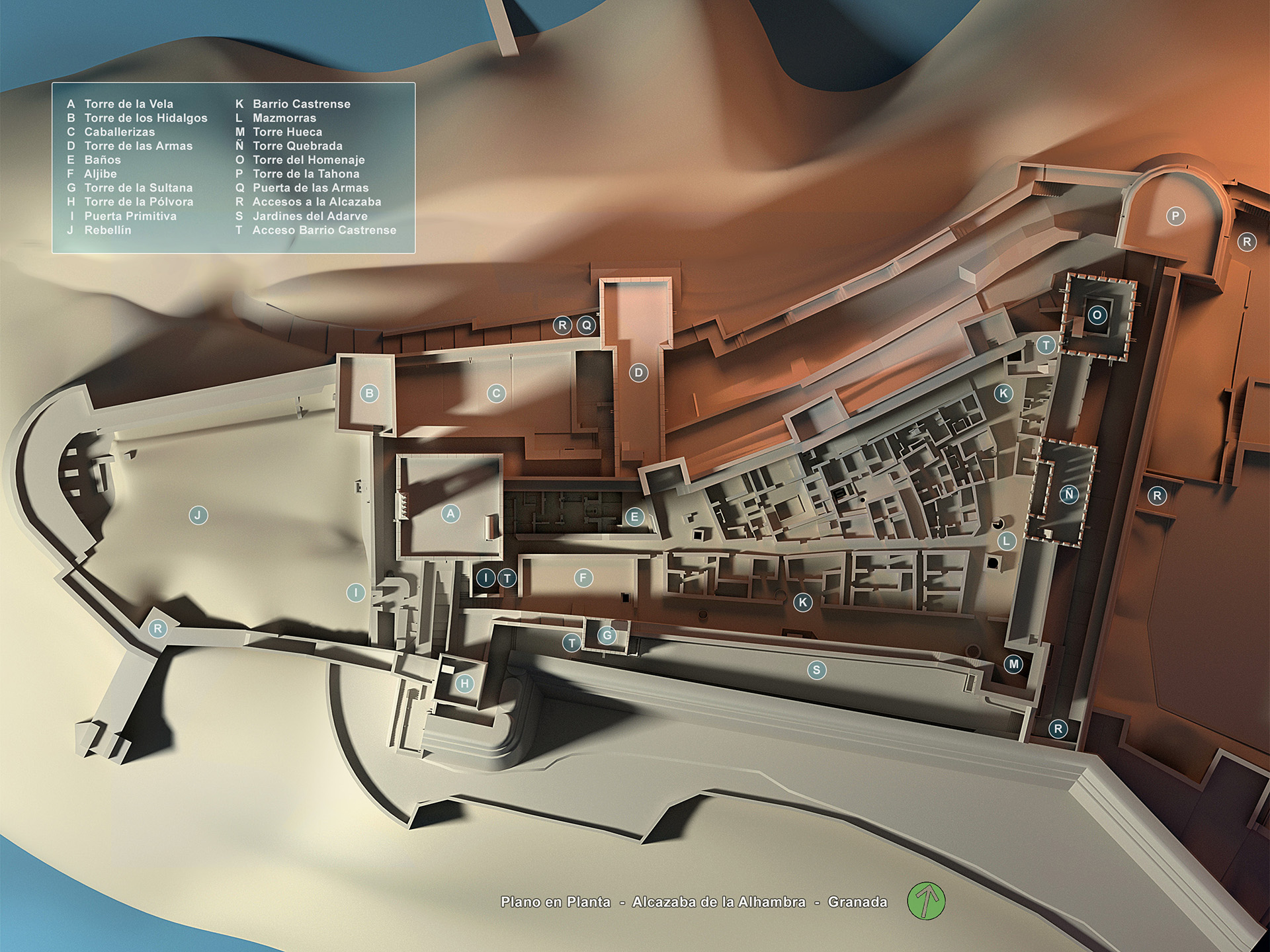

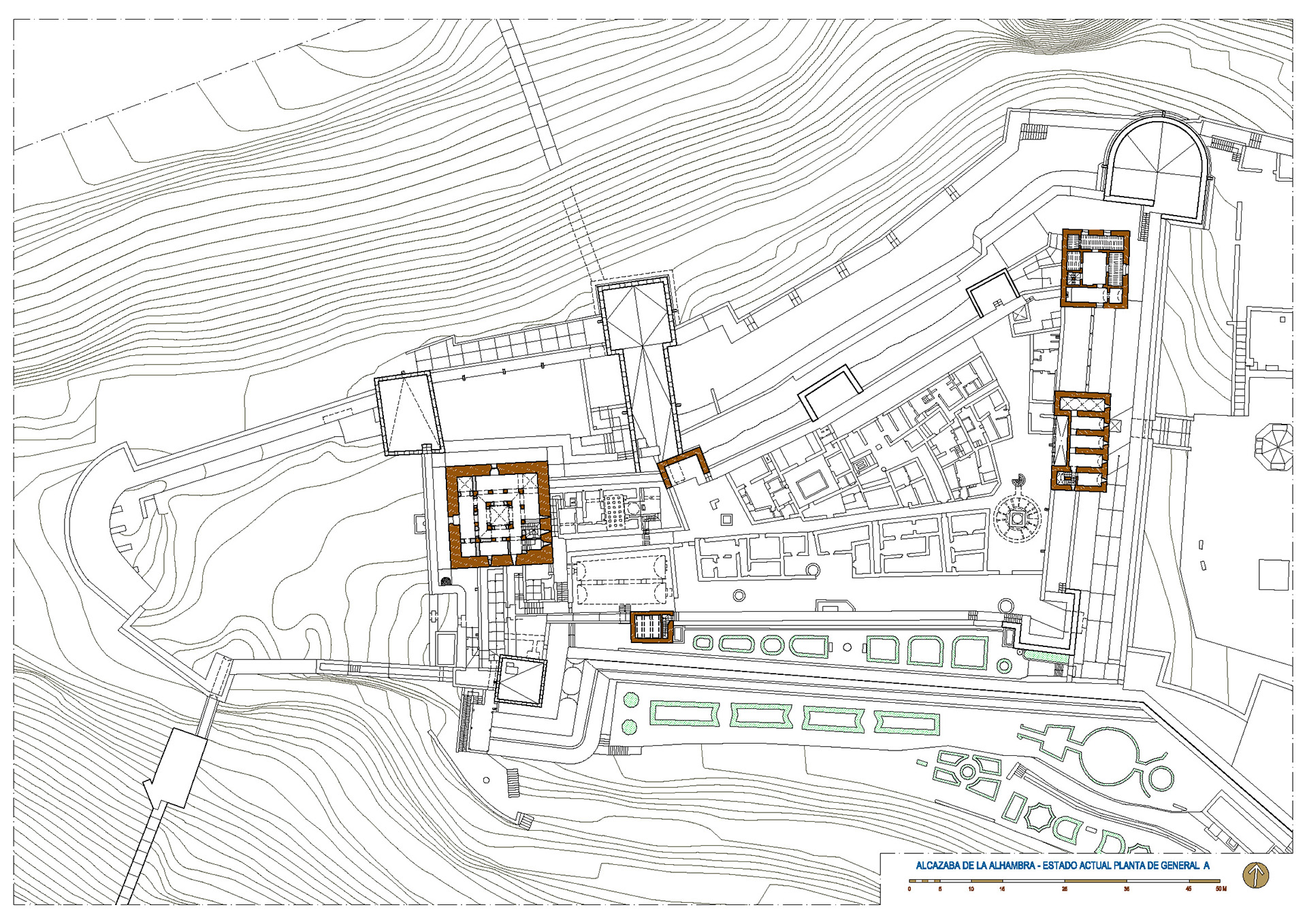

IL. 4. General Plan of the Alcazaba, 2015. Rendering , 3000x2250 pixels

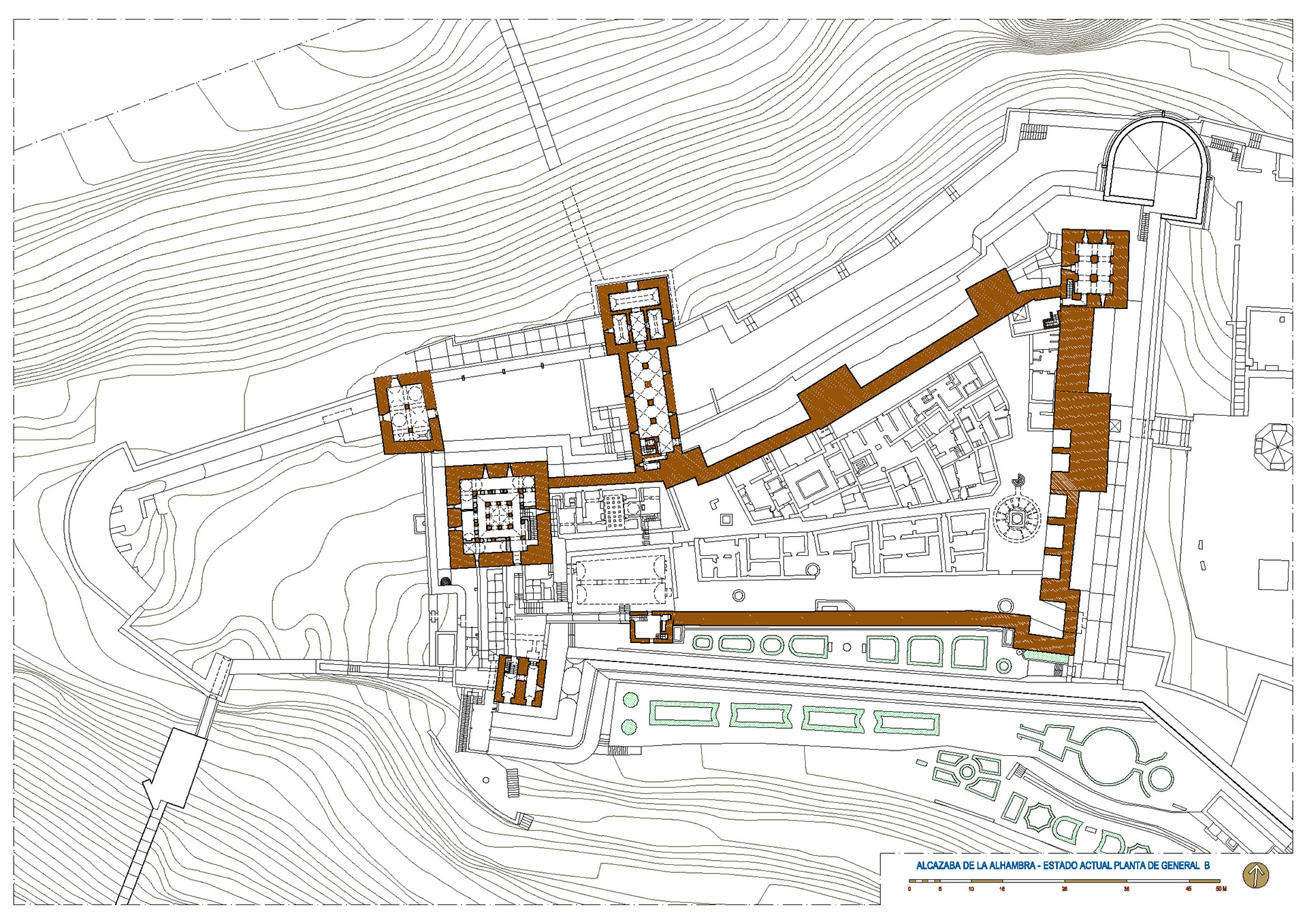

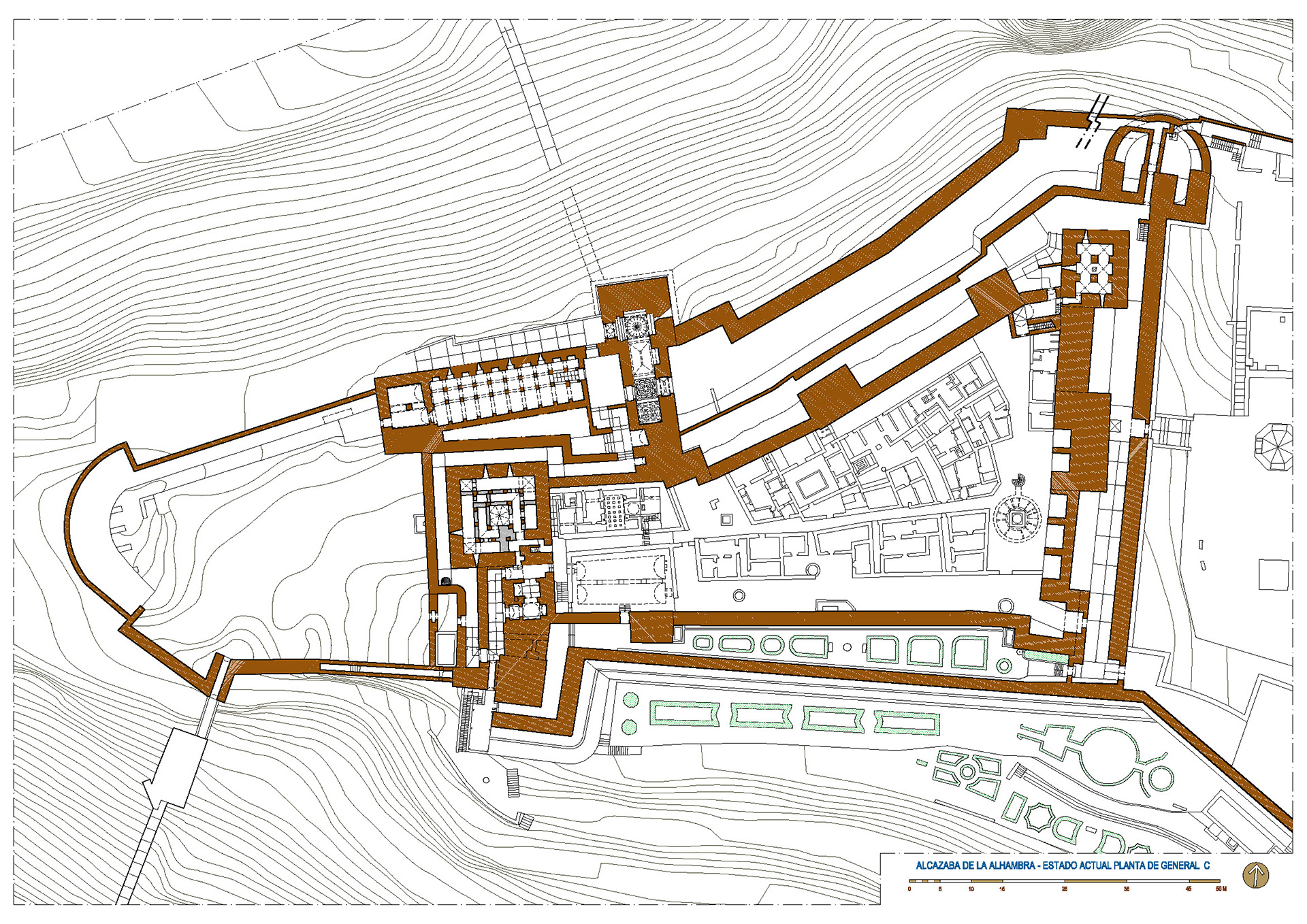

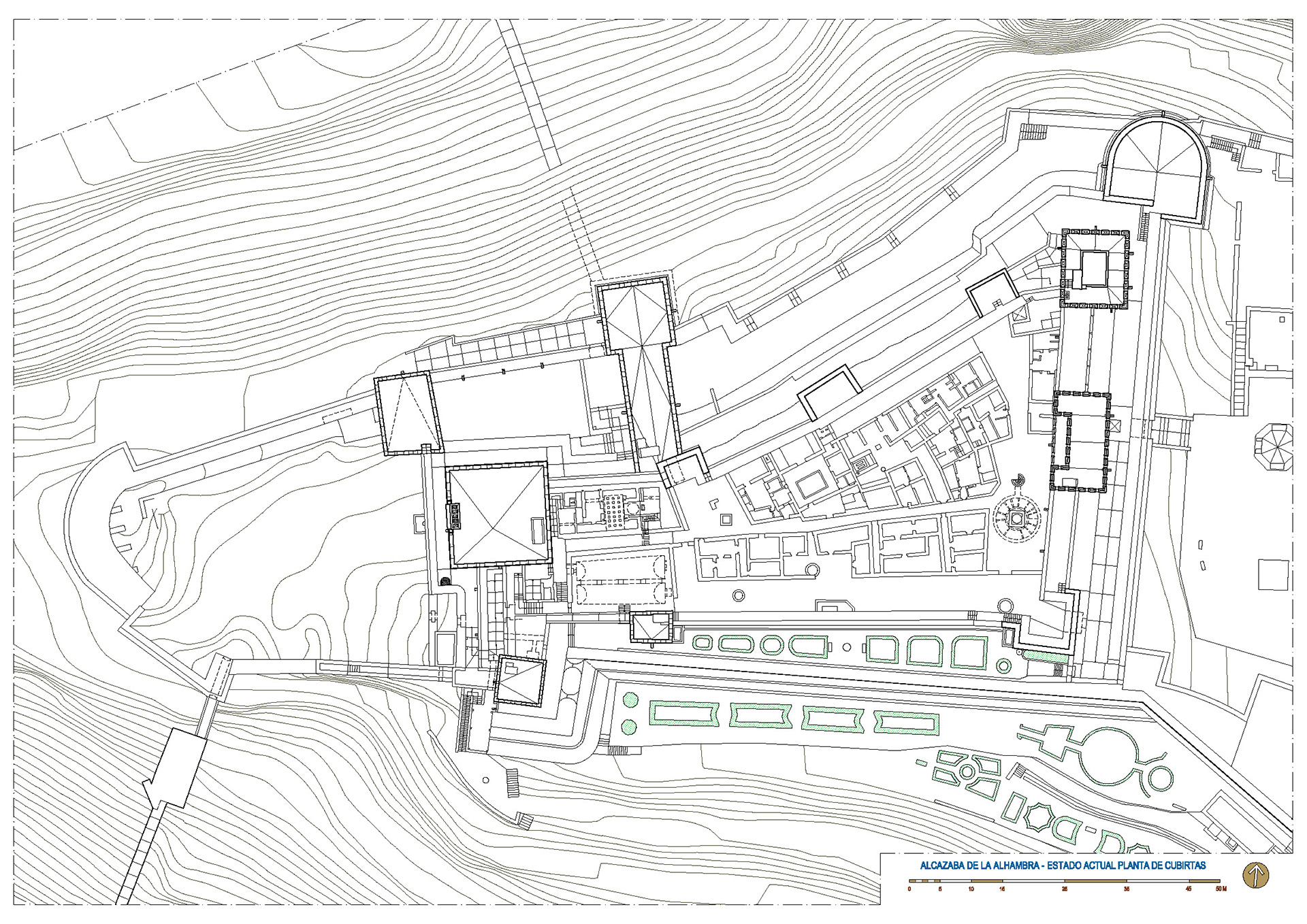

DESCRIPTION OF THE COMPLEX AT PRESENT

Before focusing on the study of the Torre del Homenaje, we will undertake a description of the Alcazaba by analyzing its physical and spatial characteristics together with their structure and functioning.

Such a description must take into account the role of the fortress, a military fortification manned by the Sultan’s guard and strategically positioned to observe and control the Alhambra citadel, the lower section of the city of Granada and its surroundings.

The premises follow a layout based on an irregular quadrilateral, the north side having a length of 100m and the east side measuring 74m. The plan becomes gradually narrower toward the west. The Torre de la Vela, the primitive gate of the fortress, the baths and the water cistern are located at the western end. On the east wall, the Torre del Homenaje stands out, together with the Torre Quebrada and Torre Hueca. Within the walls, on the parade grounds, the military neighborhood was located, which was divided into two areas separated by a long narrow street that is oriented toward the Torre de la Vela. Eleven houses of different sizes but similar structure are irregularly grouped on the north side of that street. They were the residences of the royal guard and show the typical domestic design of the Hispano-Muslim world: an angled entrance and a small patio that at the center included an element to store water –a fountain, a pond or, in one case, a pool. Depending on the size of the house, one, two or three rooms surrounded the ground-floor patio and had access to it. A narrow staircase led from the patio to the upper floor. Some of the houses faced the main street while others open onto secondary streets, but everything seems to be organized in an uncomplicated way. South from the main street there are other walls that are similar to those of the houses, although their distribution seems to be more homogeneous and regular. That has made researchers think that they may have belonged to storage buildings or used as barracks for young guards.

This space was originally the location of the military garrison’s tents although later, upon the arrival of Muhammad I, it became the site where the aforementioned houses were built. The area was buried under rubble and hidden from sight until Modesto Cendoya excavated it and recovered it between 1916 and 1918. Today, the only remains of those houses are the bases of the walls.

IL. 5. Adelaida Martín Martín. Aerial view. Torre de la Vela, 2015. Rendering, 1950x1463 Pixels

On the east, the main street ended at the large water cistern, which guaranteed the water supply to the fortress and collective baths.

The cistern was the most outstanding construction of the parade grounds. It was located at the base of the Torre de la Vela, not far from the primitive entrance to the premises. It was separated from the baths by a wide road, or main street, under which a passage way and a channel that joined both constructions crossed. The baths were built at a lower level with respect to the cistern. The cistern underwent several refurbishments in modern times, but the original two-nave structure remains, along with skylights and water conductions that reach the neighboring tower and the baths.

The baths were built by Muhammad I for the troops residing in the Alcazaba. They are attached to the Torre de la Vela and the north wall of the fortress. They are underneath the square, so their vaults and skylights were originally at the same level with it. The reason for building them underground was to make it easier to maintain their inside temperature. The skylights provided natural light and regulated both the inner temperature and humidity. Being rather small and having a simple structure, they are the oldest ones in the Alhambra. Their typology is the same as that of the 11th-century Bañuelo baths.

Both the baths and the cisterns were discovered and excavated by Modesto Cendoya between 1907 and 1909. He included them in the Alhambra plan for the first time in 1909.

At the eastern end, there are several silos at ground level that could date from the same period as the military neighborhood although, according to Antonio Malpica, it is difficult to determine this fact because of the lack of chronology supported by stratigraphic excavations. Among the towers, the one that best represents the fortified, military image of the Alcazaba is the Torre del Homenaje, at the northwest angle of the premises. Even though it is not as high as the Torre de la Vela, standing at a height of a little less than 25 meters it seems the most impressive of them all, probably due to its location 28. It is likely that, to begin with, Muhammad I established his residence there and that later the alcaides [officers in charge of the guard and defense of the fortress] lived there. The information service was located in this tower, as well as the general staff that regulated and controlled the entire defensive system of the Alhambra, including the distribution of watch duties throughout the premises. Inside, it has five storeys and a silo at the base. On the terraced roof, a small platform was used to send and receive visual signals to and from the castles and watchtowers strategically disseminated on the hills and mountains around Granada as part of the Nasrid defensive system.

The Torre Quebrada is located at the center of the eastern wall of the fortress. It has a solid structure up to the top line of the wall and from that level up it is made up of two storeys each with five rooms. The crack that gives it its name was due to the sinking of part of its upper section in 1838. This tower is an extension of the primitive Zirid tower that stands within it.

The southernmost tower (presently known as the Torre Hueca) was called Torre del Adarguero in the 16th century and it replaced a previous, smaller tower. The hueca, or hollow, of the name corresponds to the entrance to the premises from the square of the Aljibes in Castilian times.

Among all the towers, the Torre de la Vela is the one with better proportions and dimensions. Its outer image reflects the kind of architecture of great sobriety and constructive sense that characterizes the defensive structures of the Almohad period. This tower closes the west side of the defensive system facing the city and performs the function of a watchtower over the entire Vega.

Being an icon of Granada, it is one of the most relevant buildings in the Alhambra , as much for its building aspects as for its functional ones. There is a silo or dungeon at its base, and four storeys protected by a terraced roof that originally had battlements and offers the best views of the city. Its belfry holds the famous bell that gives name to the tower.

On the north wall, as mentioned, there are three small solid towers, one of which was partially destroyed to accommodate the tower-gate of the Armas. They are rectangular, have a passageway and barely project over the wall. They were built with rammed earth and gravel and covered at some points with rows of brickwork. These towers were probably built in the 11th century but the brick repair work may have been carried out in the 14th and 15th centuries.

During the Almohad period, the Torre de la Sultana (also called del Arriate and de los Adarves) was built attached to the southern wall. It is a defensive tower that connects with the Torre del Adarguero by means of a 2-meter-wide wall. Through a door to the left of its base, it works as a linking element between the parade grounds and the garden of the Adarves. It has a somewhat deformed rectangular base and it is attached to the wall along one of its longer sides. This layout is rare, differing from that of the vast majority of towers of the Alhambra.

West from the Sultana tower stands the Torre the la Pólvora, where one can read an inscription with the famous poem by Francisco A. de Icaza extolling the beauty of Granada: “Give him some alms, woman, for in life there is nothing as sad as been blind in Granada.” At present, this tower, which includes a viewpoint, gives access to the Alcazaba from the Adarves garden. It is the smallest tower in the Alcazaba and, with two doors on each of its main façades, it serves as a passageway. It is a building of high strategic value since it protects the south side of the Torre de la Vela and looks over the primitive gate and the south barbican—

under the Adarves garden at present.

The strategic importance of the tower increased from the 15th century onwards because of the advances in artillery warfare. The section of wall that connects with the Puerta de las Granadas and Torres Bermejas starts at this tower. In addition, taking advantage of the terraces in the area and using the walls of the Alcazaba, the present garden of the Adarves was built there in the 16th century.

In other words, the garden of the Adarves is a product of the transformations the Alcazaba underwent in the 16th century as a consequence of the use of artillery in warfare. In the 17th century, the Marquis of Mondéjar consolidated the garden by filling in the moat that was located between the two southern walls up to the level of the walls themselves. The impressive retaining wall that can be seen today was built against the outer wall, leaning on it. The retaining wall was built parallel to the southern wall, surrounding the Torre de la Pólvora on its west end, thus including the tower itself in the defensive system as a sort of outermost bastion.

The exact date when the platform became a garden is not known. Our guess is that it was in 1628 since one of the two fountains existing in the garden bears that date.

At first, the entire enclosure was surrounded by a barbican, which was accompanied by a moat on the east side, the weakest one 29. The depression cannot be seen today because it is occupied by the cistern under the 16th-century Plaza de los Aljibes 30. Thus, an impressive section of wall was constructed on this side before the 16th century which physically separated the Alcazaba from the rest of the citadel of the Alhambra. The natural gully and what is known as the “urban organization” square in front of the Comares palace further enhance the physical separation between the palaces and the Alcazaba.

South from the Torre de la Vela, at the center of a great depression in the terrain, the oldest door in the Alhambra is located, which used to be the main and only entrance into the premises. Before reaching it, two outer entrances had to be crossed. The first is a gate that opens up on the southern wall of the ravelin located to the west of the Alcazaba—a postern 31. The second one is on the wall that surrounds the Torre de la Vela. Once these two doors were crossed, there were two more angles to negotiate until reaching the Main door. According to Basilio Pavón, this access into the fortress is the most complicated of all that can be found in Hispano-Muslim fortifications.

This door was discovered in 1894. It is the oldest door in the Alhambra and dates from the pre-Nasrid period, perhaps the 11th century, although a unanimous opinion on the subject does not exist. Rafael Manzano says:

There is no doubt that the oldest door in the Alhambra is this one in the Alcazaba, a simple stone arch that can be a reconstruction of a 11th century entrance representing in its simplicity the old Almohad designs. It could be reached from the wall of the handaq after entering a patio where there was a pool that forced passing through two very narrow walkways, which contributed to the defensive strength. 32

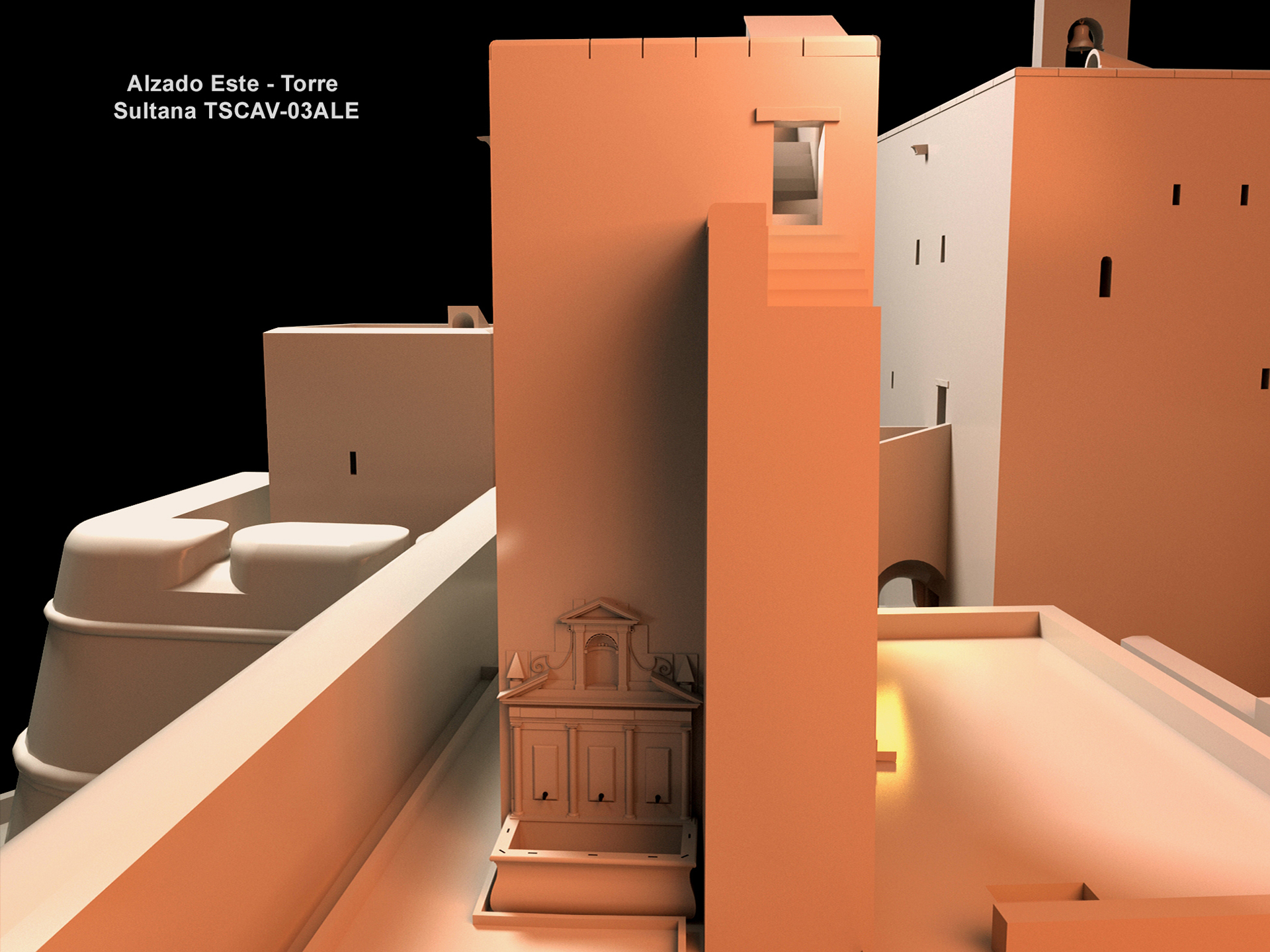

IL. 6. Adelaida Martín Martín. East elevation: Torre de la Sultana, 2015. Rendering, 1950x1463 pixels

IL. 7. Adelaida Martín Martín. Outer view from the west. Primitive door, 2015. Rendering, 1950x1463 pixels

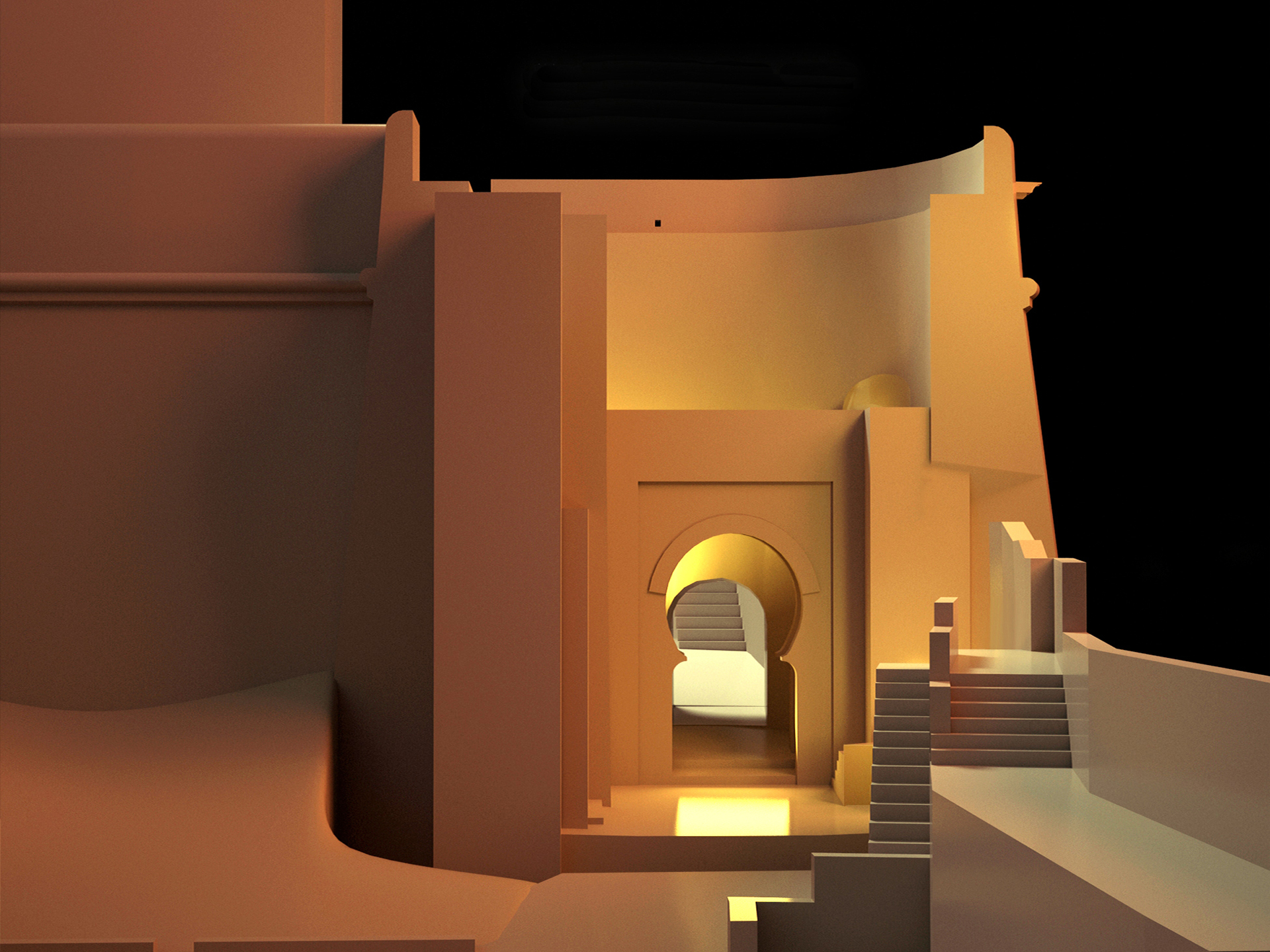

At the end of the 13th century the Gate-Tower de las Armas was added to the premises with the idea of communicating the city of Granada with the Alhambra palaces. This albarrana tower was built over a small pre-Nasrid tower, as we have mentioned. From it there are two possible itineraries: one follows the barbican that runs parallel to the Torre de la Vela to enter the Alcazaba through the Main door, and the other goes around the fortress using the alley that goes to the Puerta de la Tahona.

It is very likely that second access was conceived in relation to the primitive palaces of the Alhambra assigned to Muhammad III. In this way, the visitor was able to choose between going into the area of the palaces or entering the fortress.

Besides these gates and coeval to the Armas gate-tower there is also the so-called Puerta de la Tahona, which has already been mentioned. It was located between the barbican and the northern wall and allowed direct access by communicating the Alhambra with the alley the surrounds the Alcazaba on the north side until reaching the Tower-Gate de las Armas.

At present, the Tahona gate cannot be seen because it is hidden by the 16th-century Torre del Cubo, which was built in more modern times to serve as an artillery emplacement. The door that can be seen today is a modern reconstruction of the original. Access to the palaces through it was granted by means of a perforation on the foundations of the Cubo bastion carried out in the 16th century.

In 1929, Leopoldo Torres Balbás repaired the Cubo although it was Jesús Bermúdez Pareja who was responsible for its excavation and found the Tahona door from the Islamic period. Hidden inside the Christian building—the Cubo, the door was discovered after the decision was made to remove the infill material within the space between the Alcazaba and the area of the palaces between 1951 and 1954.

In order to provide the 13th-century Alhambra and the Alcazaba with some sort of unity, the north side of the latter had to be modified by adding new entrances. Nevertheless, the function of the fortress—the defense and security of the Sabika—was always kept in mind. That was how the Puerta de las Armas and the Puerta de la Tahona came to be. 33

Independently from the date and origin of the door, it is clear that the Nasrids used it to close-off the northern end of the Alcazaba. In addition, by means of the Torre del Homenaje, that same front was reinforced and the river basin was controlled. In that area, the small Zirid towers were not replaced with others since the dramatic cliffs on which they were built seemed to guarantee sufficient defense.

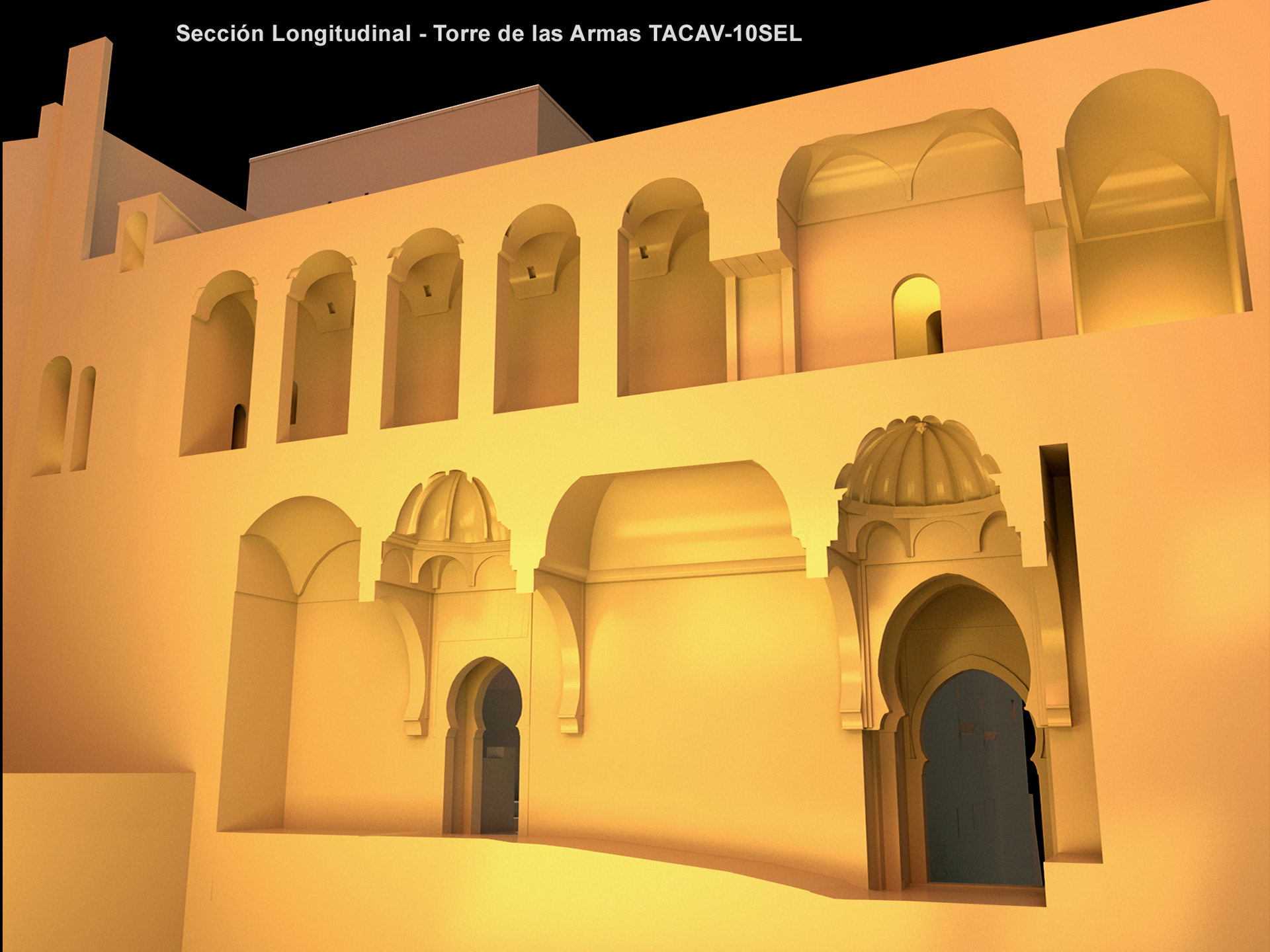

IL. 8. Adelaida Martín Martín. Longitudinal section-Torre de las Armas, 2015. Rendering, 1950x1463 pixels

One other fundamental element for the defense of the entire citadel of the Alhambra and closely connected with the Alcazaba was the outer wall of the complex, which is very well preserved. The wall was entirely erected over the edges of vertical cuts in the terrain and path was designed along it serving as a kind of street surrounding the settlement. The upper chemin de ronde of the wall that encloses the Alhambra connects by means of posterns with the Alcazaba barbican. This wall-walk starts at the southeast angle of the premises and surrounds the palaces until it runs into the Torres de las Armas without an access into it. Thus, in order to enter the barbican of the Alcazaba, the wall-walk connects with the Torre del Homenaje, which allowed the guards to go around the palaces and to patrol without entering palace grounds 34.

As for the barbican, it virtually surrounded all the premises uninterruptedly until the Gate-Tower de las Armas was built. In later years a number of reforms were carried out to the south, by the Torre de la Pólvora.

Being protected from strong winds, the barbican on the south side was changed into the Garden of the Adarves in the 17th century . . . At the north and south ends of the eastern side of this construction, the general premises of the Alhambra connected through gates that were reinforced with small towers. Of all those gates, the only one remaining is the one hidden by the Cubo by the Puerta de la Tahona. The one at the south end and its small tower disappeared, being replaced by the opening that, latter fitted with a door, is used as an entrance by visitors. 35

The ravelin at the west end of the Alcazaba was introduced into the defensive system of the Alhambra during a later period. It was built in Castillian times as a means of adapting the defensive system of the military premises to artillery warfare 36. Near it there are two water cisterns, one of which—the one by the Torre de la Vela, was probably built before the exterior fortification Itself. The second one is located outside the northwest section of the fortification. It is important to keep in mind that the ravelin is in contact with the wall that ever since the 11th century had joined the Alcazaba and the castle of Mauror, as part of the defensive system and allowing passage through its wall.

Going back to the Puerta de las Armas, two openings can be seen after it is crossed. To the back on the left-hand side, there is the door to the street that leads to the palaces. Opposite, there is an arch leading to a square that the Nasrid transformations turned into a sort of inner courtyard. The door opening to the square opens at ground level, which makes transit on horseback possible and favors the location of the horse stables in this area.

The stables were originally designed to be larger than the space that can be observed at present, but they had to be refurbished and were made smaller after a landslide on the north slope of the Sabika. According to Gómez Moreno Martínez, they were refurbished once again in the 16th century. Today, the narrow central section of the entrance can still be appreciated, as well as the way in which the horses were kept in two large areas with mangers on both sides, even though the northern space is almost completely destroyed. The primitive entrance to the stables faces the east. On the west side, the stables join the two-storied Torre de los Hidalgos, which was built by the Moriscos and communicates with the stables through the ground floor.

Even though we have described the entire premises, there is an element that is essential to understand the relationship between the Alcazaba, Palaces and Saria, and this is the square located opposite the palaces and that can be entered from the Puerta de la Tahona. Until the 1950s the square went all the way up to the northern wall. However, the archaeological excavation work directed by Jesús Bermúdez Pareja between 1951 and 1954 and the removal of the rubble forced its modification in order to recover an important sector of the Alhambra that had been hidden and unknown until then. Once the level of the ground was lowered, it was assumed that in the Muslim period the area was occupied by a large square on the north side and a gully on the south side and there was a separation between the Alcazaba and the palaces consisting in a wall and perhaps a couple of towers. The square, known as the “urban organization” square, was the space through which the entire urban distribution of the Alhambra was organized; the whole street network of the premises was given an orderly structure in relation to it. Most probably, in Nasrid times, the street called Real Baja began in the square and ran to the Puerta del Vino parallel to a wall that has disappeared and had two doors, a lower one in the ravine and another one on higher ground with its own small square, the Puerta del Vino.

IL. 9. Adelaida Martín Martín. Longitudinal section-Tahona and Cubo, 2015. Rendering, 1950x1463 pixels

DESCRIPTION OF THE TORRE DEL HOMENAJE

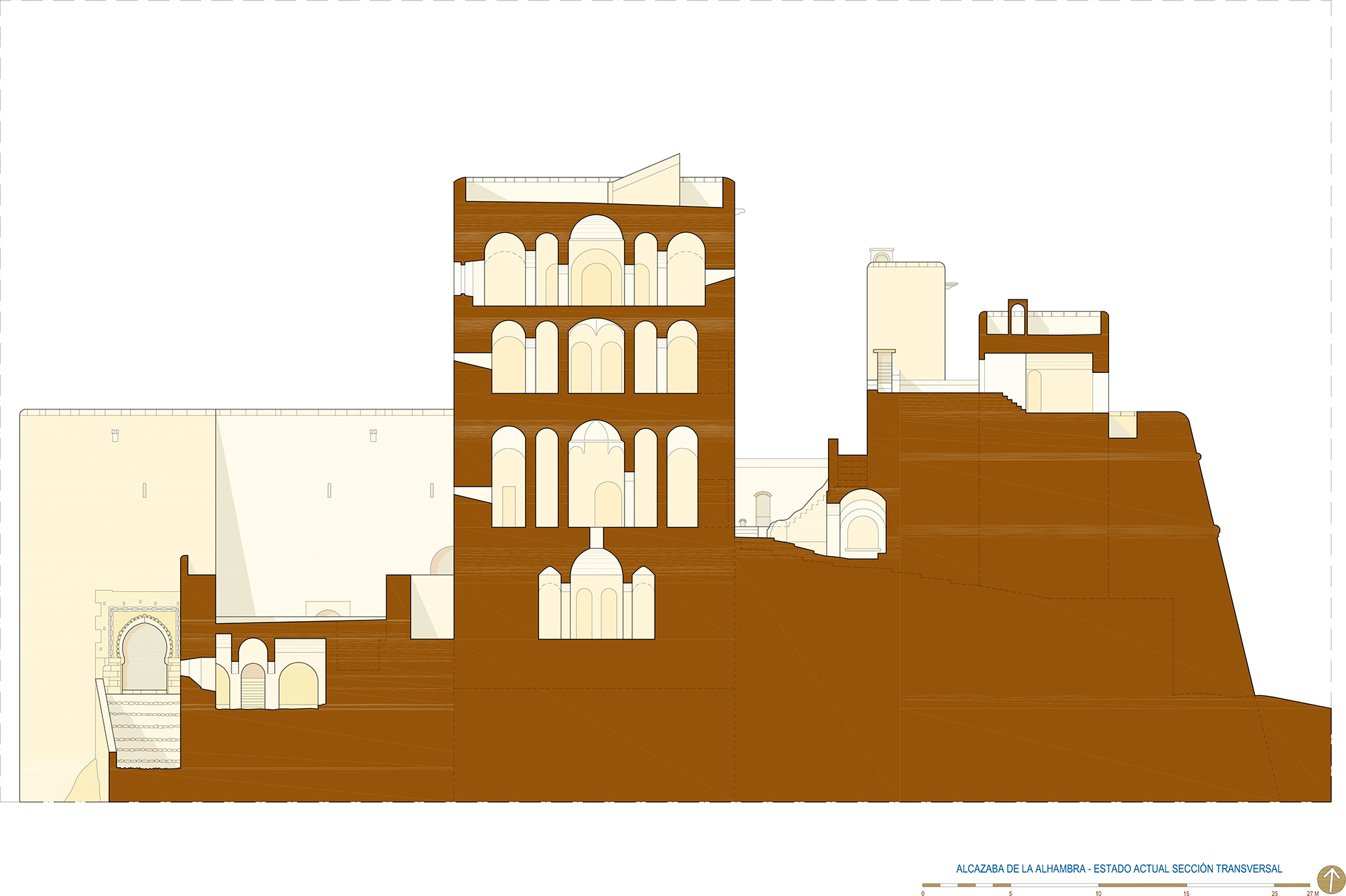

The Torre del Homenaje was built in the 13th century, so it is almost contemporary to the Torre de la Vela. Some scholars argue, however, that it was built later since some structural errors that can be observed in the Torre de la Vela were corrected in the Torre del Homenaje 37.

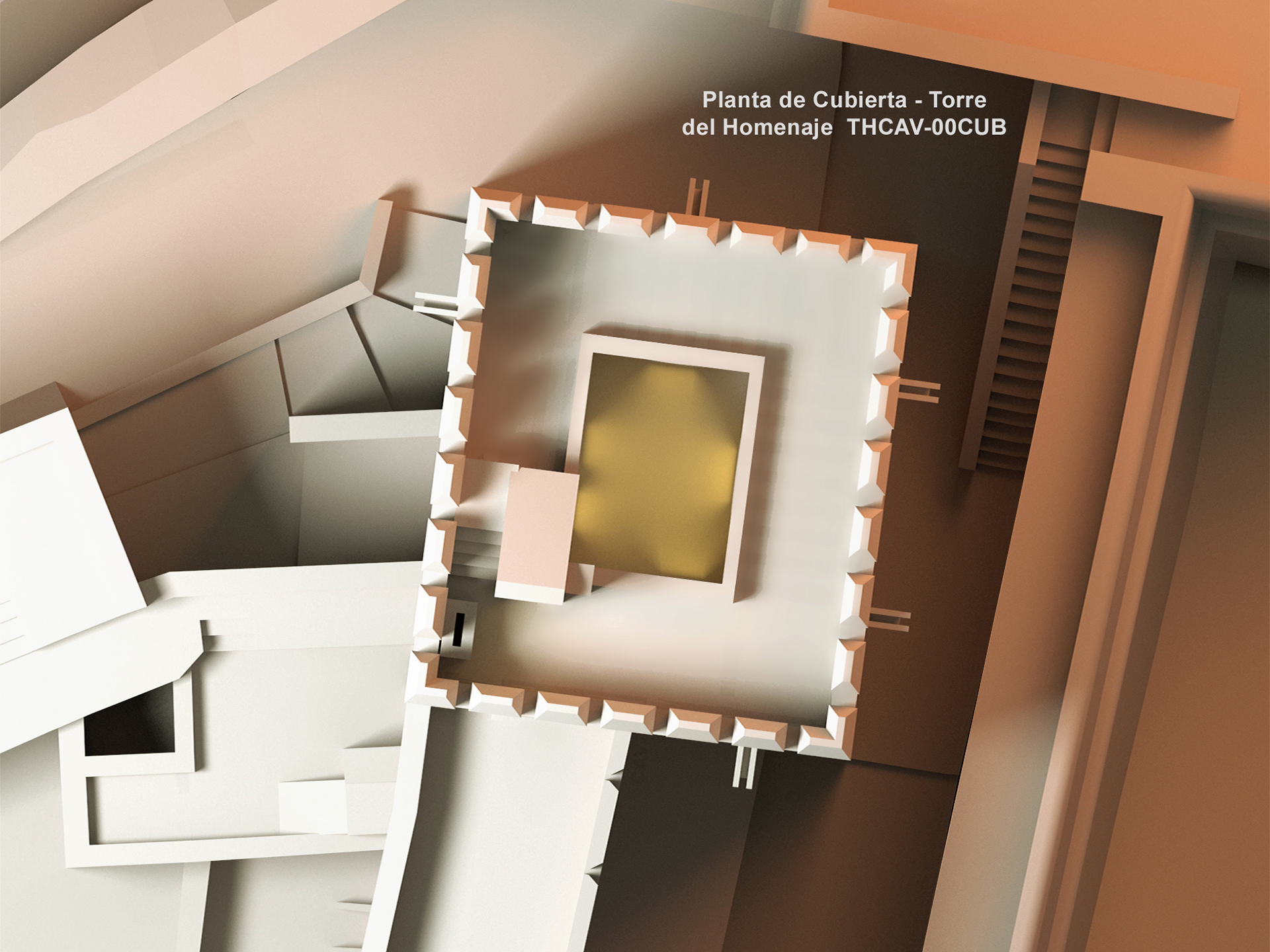

This tower occupies the northeastern angle of the Alcazaba and includes a residence on the upper floor (level 5). At a height of almost 25 meters, it was designed with a rectangular plan measuring 12.12 meters by 10.46 meters and, in spite of the fact that is not as high as the Torre de la Vela, it ends up being the most spectacular tower in the entire fortress since it sits on higher ground. Actually, the highest point in the fortress is located on terraced roof and, from there, visual contact can be made with the watchtowers scattered on the surrounding mountains. The center of operations for the defense of the Alhambra was located in this tower, which makes it the most important one strategically.

Originally built in rammed earth, at present it shows boxes of bricks and masonry work with large rounded stones on the upper sections of its exterior façades. There are no remnants of a possible original outer finish. In addition, it shows vestiges of old shoring-up structures in the lower sections.

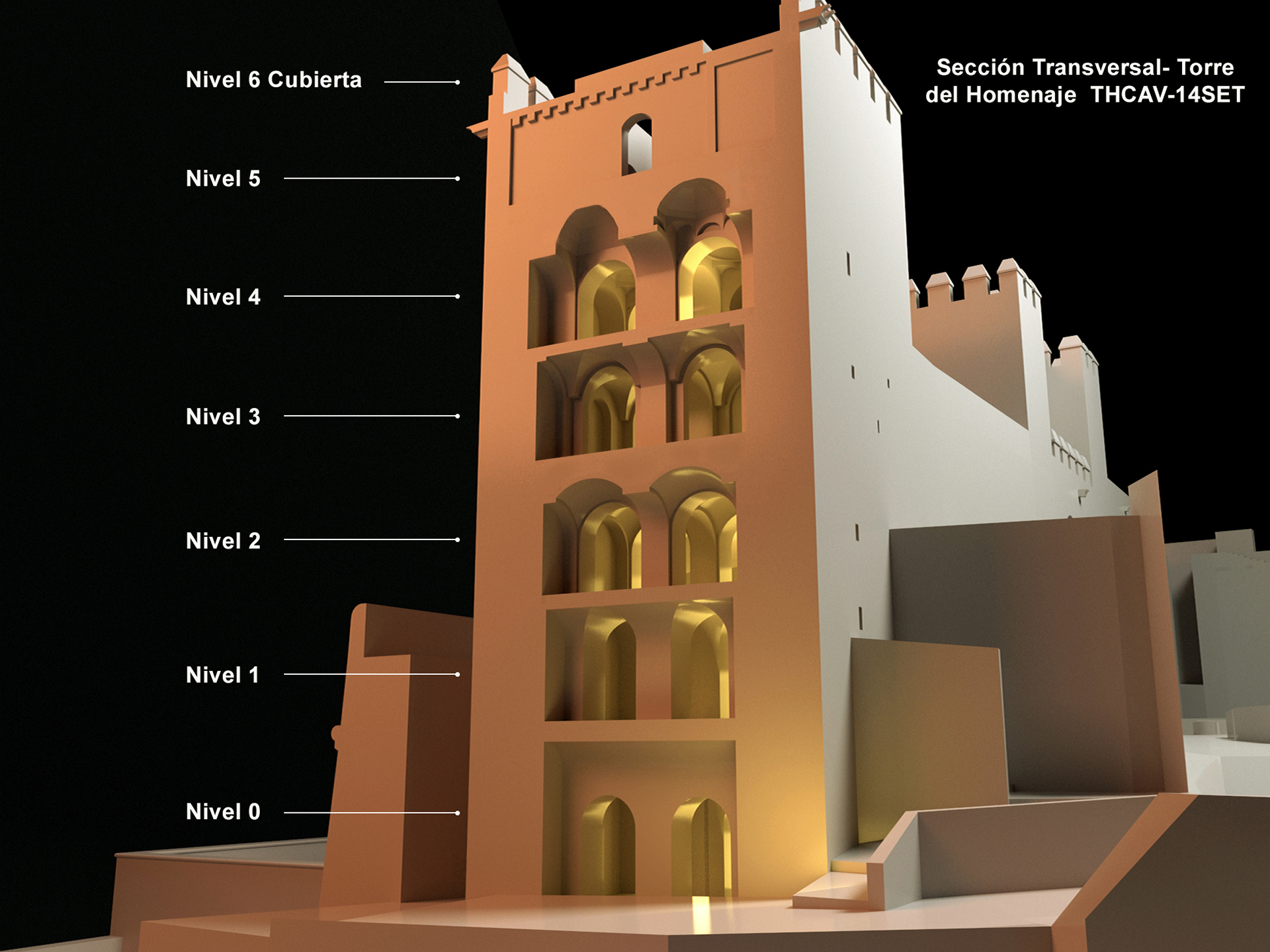

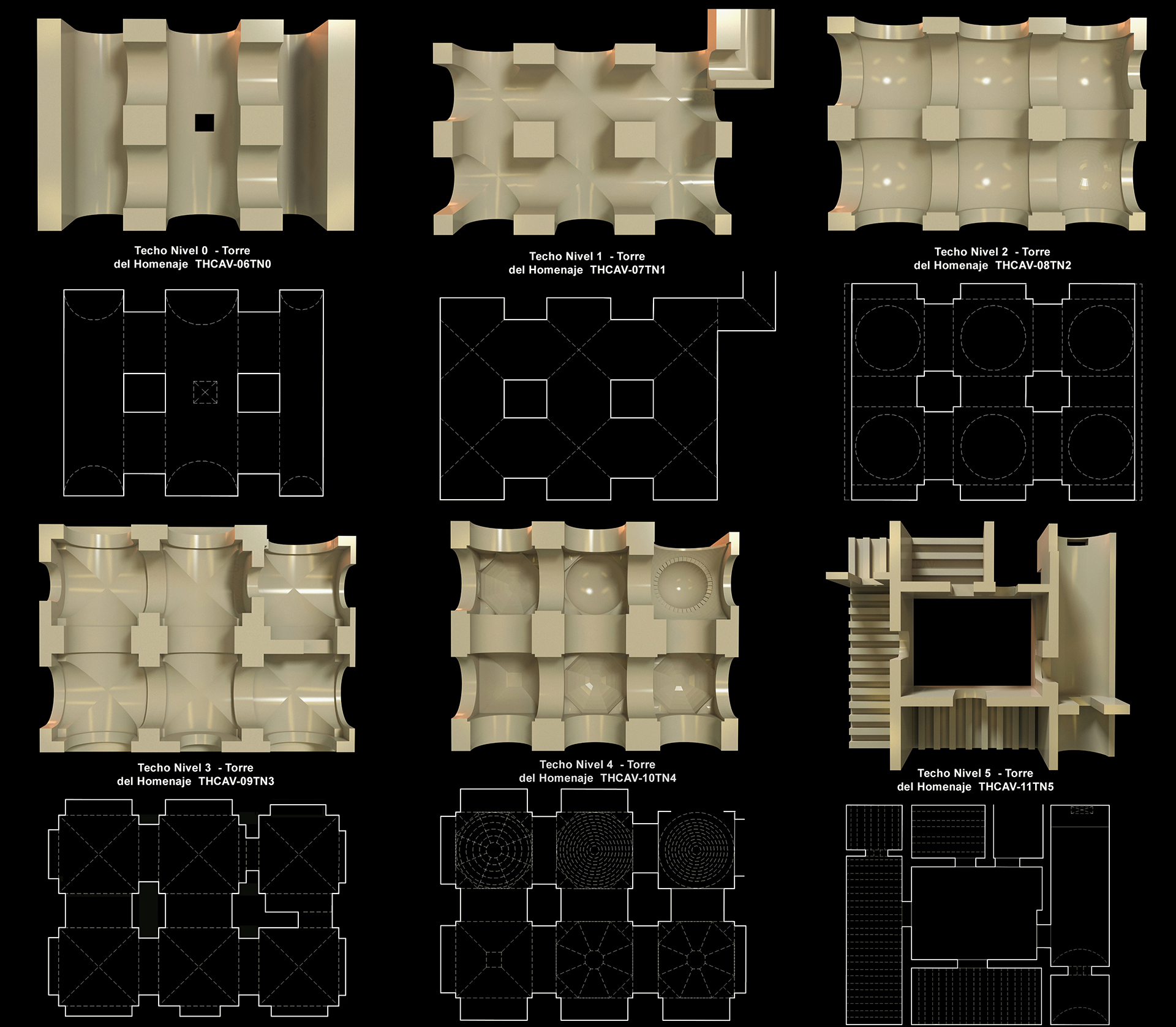

The inside of the tower is characteristically divided by arches, showing a great variety of vaults, and it has two pillars in the center that go all the way up until the last level, where there is a patio. It has six storeys (level 0-level 1-level 2-level 3-level 4-level 5) that present unique variations in the distribution of their vaulted spaces.

Except for the levels 0 and 5, the rest of the floors are designed with six vaulted spaces and windows on the façades but for the eastern one, which was considered the most vulnerable to enemy artillery.

The basement (level 0), was originally used as a storing facility to keep grain, salt and spices, but became a dungeon with the passing of time. This space is accessible from the level 1 by means of a trapdoor, therefore a rope or ladder was necessary in order to enter or exit the space.

The tower has three independent entrances:

Access to the level 1 is from the passageway atop the north wall after having previously gone through a section covered with a barrel vault. At this level the opening to access the tower shows a wooden lintel and a door frame including hinge stones on the inner side of the tower wall.

Level 2, which does not communicate with level 1, is entered from the north wall. The stairs to the other levels are located on the southwestern side of the tower. This floor becomes the model for the upper levels: six square or noticeably rectangular spaces separated by cross-shaped pillars and semicircular arches 38.

On level 4, there is yet another access door of to this tower that communicates with wall-walk atop of the eastern wall. It is not known whether this door is from the time when the tower was built or if it was added later, when the east wall was reinforced and reconstructed in the 14th century. Regardless of this, neither can we determine if the original wall reached this level or whether this door was opened after the Torre Quebrada was built in order to communicate both towers.

Structurally speaking, it is worth mentioning that, as it is also the case with the Torre de la Vela, the walls become thinner as they rise. The wall at the first level is 2.35 meters wide, while it is 0.80 meters wide at the uppermost level.

Description of each level

Level 0 is organized by means of three large rectangular spaces covered by barrel vaults that follow the east-west direction. The central space is larger than the side spaces, and the one to the south is the smallest of the three. Passage from one space to another is provided by four arches that are supported by the central pillars and the east and west walls. The vaults, arches and pillars were built with bricks, the jointing has the same width as the thickness of the bricks themselves.

Access to the level 1 door is granted after negotiating the last angled entrance to the Alcazaba under the north wall and by escalating six steps. The steps are made of bricks laid at header course, except for the first and last steps, which are made out of stone. Once the door is crossed, the main space is entered through an L-shaped corridor that is covered by a barrel vault set within the south wall. The entire floor is organized into six spaces, as a result of the intersection of the barrel vaults, which creates six groin vaults. This storey differs from the others in that between its pillars there are no supporting arches. The vaults rest directly on the north and south walls, and on pilasters on the east and west wall. Light comes through embrasures to the north, south and west. The floor is finished off with medium size brick and stone fragments. At the center, there is the trapdoor that goes to the level 0, covered with a floor tile framed with stones.

Level 2 is entered from the wall-walk on the north wall after going through the angled entrance underneath it and ascending a steep staircase located within the wall. The steps start at the level of the parade grounds and are made with bricks laid at rowlock course. After crossing the door and going through an angled corridor that is covered with a barrel vault within the south wall of the tower, we enter this level. The door is similar to the one on level 1 although it has stone jambs. This floor is organized into six spaces covered with sail vaults that lean directly on the north and south walls, the central pillars and the pilasters on the east and west sides. The pillars at this level are perfectly cruciform because the arches are of the same width in both directions. The entire space receives light from windows on its north, south and west walls. In five of the six sections that are defined by the vaults and arches, the floor is made out of bricks laid at soldier course while in the sixth space – in the southeast area—the material used is brick and stone. Originally this whole space was painted and ornamented, even the vaults, but presently both the finishing material and the floor are rather deteriorated.

The staircase that gives access to the level 3 is inside the eastern wall of the tower. To reach it, one has to cross the entrance to the second level and leaving it on the right. On level 3, there are six spaces that are noticeably rectangular and covered by groin vaults. The arches oriented in the north-south direction are wider than the ones that run from east to west. Another element that makes this level different from the lower one is that there are pilasters not only on the east and west walls but also on the north and south walls. The space is lighted by means of two openings on the west and south façades.

One more remarkable difference between this level and the other ones is the fact that the first space is independent from the others and was delimited by doors, of which only their lintels remain. The floor was covered with ceramic tiles that were laid following a herringbone pattern in the area closer to the stairs and in the other areas laid in a running bonds perpendicular to each other. The finishes of the walls and ceilings are tarnished due to the smoke from fires that were lit in this space at different times.

On level 4 there are six spaces again, but this time, for aesthetic reasons, a variety of vaults were used. There are eight-sided domical vaults supported by pediments, simple domical vaults and sail vaults set on pediments.

On the fifth floor (level 4) there is more variety. The three [vaults] to the west are identical to each other—pendentive domes set on segmented arches. The rest are: a normal domical vault, another domical vault that presents eight sections set on segmented pendentives like the first three, and the last one, a sail vault with an octagonal base and the same pendentives, providing an agreeable visual effect. On the second and fourth levels there are small windows, like embrasures, with lintels of cheap boards and set toward the inside. The sixth floor has undergone some reforms and is different from the others. It has a sort of patio in the center and rooms around it. Of these, only one still maintains its barrel vault, which is low and has been built with bricks set the other was around and plaster. One suspects that the other elements collapsed and were rebuilt with flat timber structures covered with mortar in Christian times. 39

Like on the lower level, supporting arches are aligned in both directions and there are pilasters on all four sides. The arches in the north-south direction are bigger, which generates rectangular cruciform pillars. The lack of symmetry of the pillars and pilasters makes it possible to perceive the assortment of domes in the square spaces and the different heights that the variety of vaults permits in each space.

Light is brought into this level by means of two windows on the north side, one on the west side and another on the south wall. Here the flooring has been set on a herringbone bond, and it is nearly perfectly preserved. There are traces of whitewash and painting on the brick walls and on some of the vaults.

IL. 10. Adelaida Martín Martín, Plan of the present state, Alcazaba (A), 2015. Planimetry, 2339x1654 pixels

IL. 11. Adelaida Martín Martín, Plan of the present state, Alcazaba (B), 2015. Planimetry, 2339x1654 pixels

IL. 12. Adelaida Martín Martín, Plan of the present state, Alcazaba (C), 2015. Planimetry, 2339x1654 pixels

IL. 13. Adelaida Martín Martín, Plan of the present state, Alcazaba (Roof plan), 2015. Planimetry, 2339x1654 pixels

IL. 14. Adelaida Martín Martín, Plan of the present state, Alcazaba (Cross section), 2015. Planimetry, 2339x1654 pixels

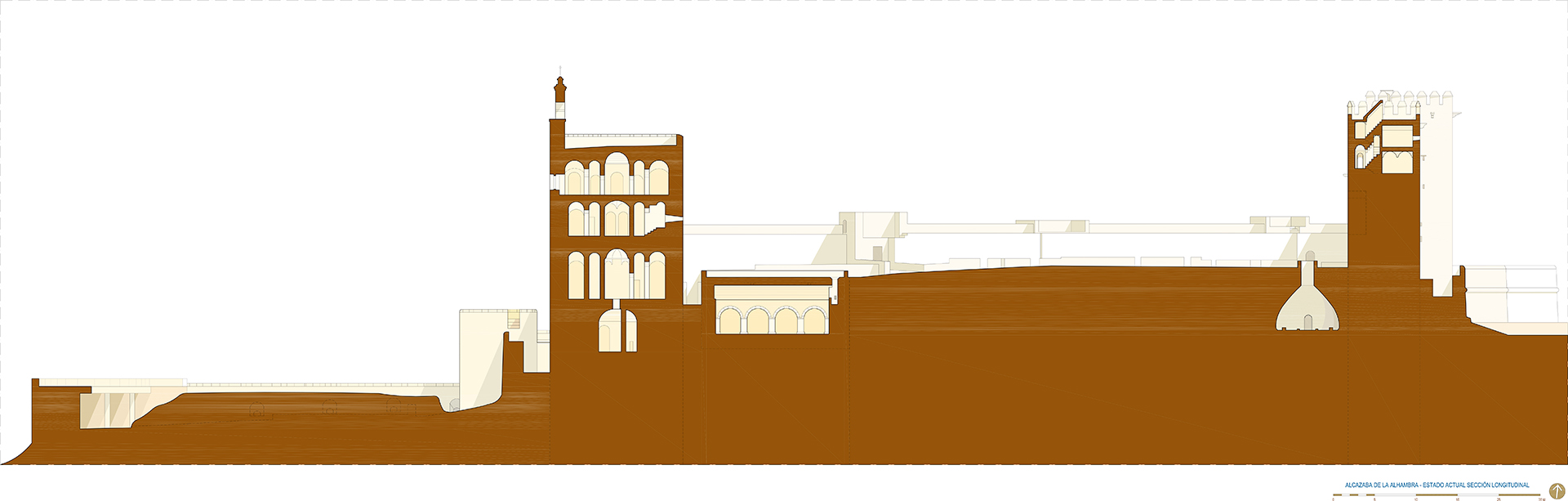

IL. 15. Adelaida Martín Martín, Plan of the present state, Alcazaba (Longitudinal section), 2015. Planimetry, 2339x1654 pixels

The door that goes from the fourth level to the passageway on top of the fortress wall is worth mentioning. The opening was designed with a false 90-centimeter-high lintel and exposed brickwork on the outer side. Having the shape of an inverted trapezoid, the brick lintel rests on another wooden lintel, with jambs, and it used to crown a door that has since disappeared.

From the forth level, one go up to the residence installed on the fifth floor, which replicates the plan of the houses built on the parade grounds 40. This space in the Torre del Homenaje is the first known residence located in a tower that can be found in Hispano-Muslim architecture. The dwelling is laid out into rectangular rooms around a patio. The only original room remaining is on the south side, which is covered by a barrel vault made with exposed bricks, like the ones used to cover the inside surface of the rammed earth-and-gravel walls. The rest of the rooms, which probably had the same sort of ceiling, at present show sets of beams supporting a flat roof structure. The intervention to reconstruct these structures on the fifth floor, took place under the direction of Mariano Contreras in the 19th century. From this level , the roof top of the tower is accessed by the staircase that continues from the lower levels . The terraced roof is surrounded by battlements that were built, due to the disappearance of the original ones, following a design by Mariano Contreras.

The lintelled openings in the north and south elevation level are larger at this level than those on the other storeys. The floor is covered with ceramic tiles that were set following different designs.

As for the materials used in the construction of this tower, it can be said that rammed earth with lime was used for the exterior walls, while bricks were preferred for the inner structural elements, such as pillars, arches and vaults. As mentioned above, several kinds of floor finished were used, with the choice of several solutions involving stones and ceramic tiling.

IL. 16. Adelaida Martín Martín, Location of the Tower Of The Homenaje, 2015. Rendering, 2067x1150 pixels

IL. 17. Adelaida Martín Martín, Cross section. The Homenaje, 2015. Rendering, 1280x960 pixels

IL. 18. Adelaida Martín Martín, Roof plan. The Homenaje, 2015. Rendering, 1280x960 pixels

CONCLUSIONS

La Alcazaba (al-Qasaba al-Hamra) came to be following orders by Muhammad I for the reconstruction of some previous fortified premises (Hisn al-Hamra’)on the Sabika hill.

The move from the Alcazaba Qadima (Granada) to the fortress on the Sabika was due to reasons of space and defense. The premises acquired an urban character when Muhammad I decided to provide the hill with water, thus making it possible for the site to be settled and developed as a citadel. But for the creation of a hydraulic system that brought water up from the Darro River to the Sabika hill, Madinat al-Hamra would have been a clear example of an habitat bound for ruin and forsakenness.

Most likely, the entire Alhambra premises were fortified by Muhammad II and Muhammad III by means of small rammed-earth towers that, hypothetically, were later modified by Yusuf I (1333-1354). At the end of the 13th century, the entire complex was protected by a wall.

It could be said that Madinat al-Hamra originated as a product of military architecture (al-Qasaba al-Hamra), and that it later to developed into a mix of military and courtesan architectures (palaces, residence towers and defensive gates). The al-Qasaba al-Hamra stood like an appendix on the west end of the citadel.

With its residence towers and defensive systems, such as walls and barbicans, al-Qasaba al-Hamra was probably finished during the first Nasrid period—between the reigns of Muhammad I and Yusuf I. By contrast, it is difficult to determine the exact chronology of the water cistern, the baths and the residences that make up the military neighborhood. It is likely, however, that they were built during the same period or some of them even before, during the 11th century.

With the Nasrids, the al-Qasaba al-Hamra changed spatially and functionally, becoming a medina (Madinat al-Hamra) and developing, as we have shown, along the clear, pre-established guidelines: Hisn al-Hamra.

The Torre del Homenaje is one of the most emblematic defensive buildings among Hispano-Muslim fortresses because of its context, design and building techniques. In addition, it is the first known tower with a residence incorporated from the Hispano-Muslim period.

The tower presents architectural work of great sobriety as well as the building sense that characterizes Almohad defensive structures, its monotonous exterior image being in direct contrast with the diversity of the vaults spaces within. Most likely, it was built during Muhammad I’s rule over a tower from then Zirid period. The main use of the tower was to strengthen the northeast end of the Alcazaba and control the basin of the Darro River.

The exterior image of the Alcazaba is its main feature because it does not hide its nature; on the contrary, it shows it. The materials used accompany its form from its very conception, reflecting its structural and constructive functioning. The forms correspond to a deep knowledge of the building systems that give consistency to the use of the materials 41.

In the Alcazaba, the volume of natural stone materials is minimal when compared to artificial materials: rammed earth, bricks and mortar. The use of mortar in combination with rammed earth produces strong, solid walls thanks to a mixture of gravel, sand, ferruginous clay and lime. The use of bricks, especially in pillars, arches and vaults is another aspect of this architecture.

We hope that the present work will contribute to clarify the subject and simultaneously offer a new view on the Alcazaba. We have re-drawn existing planimetry by using 21st-century techniques, showing our conclusions on new techniques of our own elaboration. We would like to think that this colossal effort will help to show and give the relevance that it deserves to one of the best Hispano-Muslim alcazabas, one that seems to sleep in the shadow castby the Alhambra palaces waiting to be moved front and center of historical studies, where the entire world will be able to admire its worth and beauty.

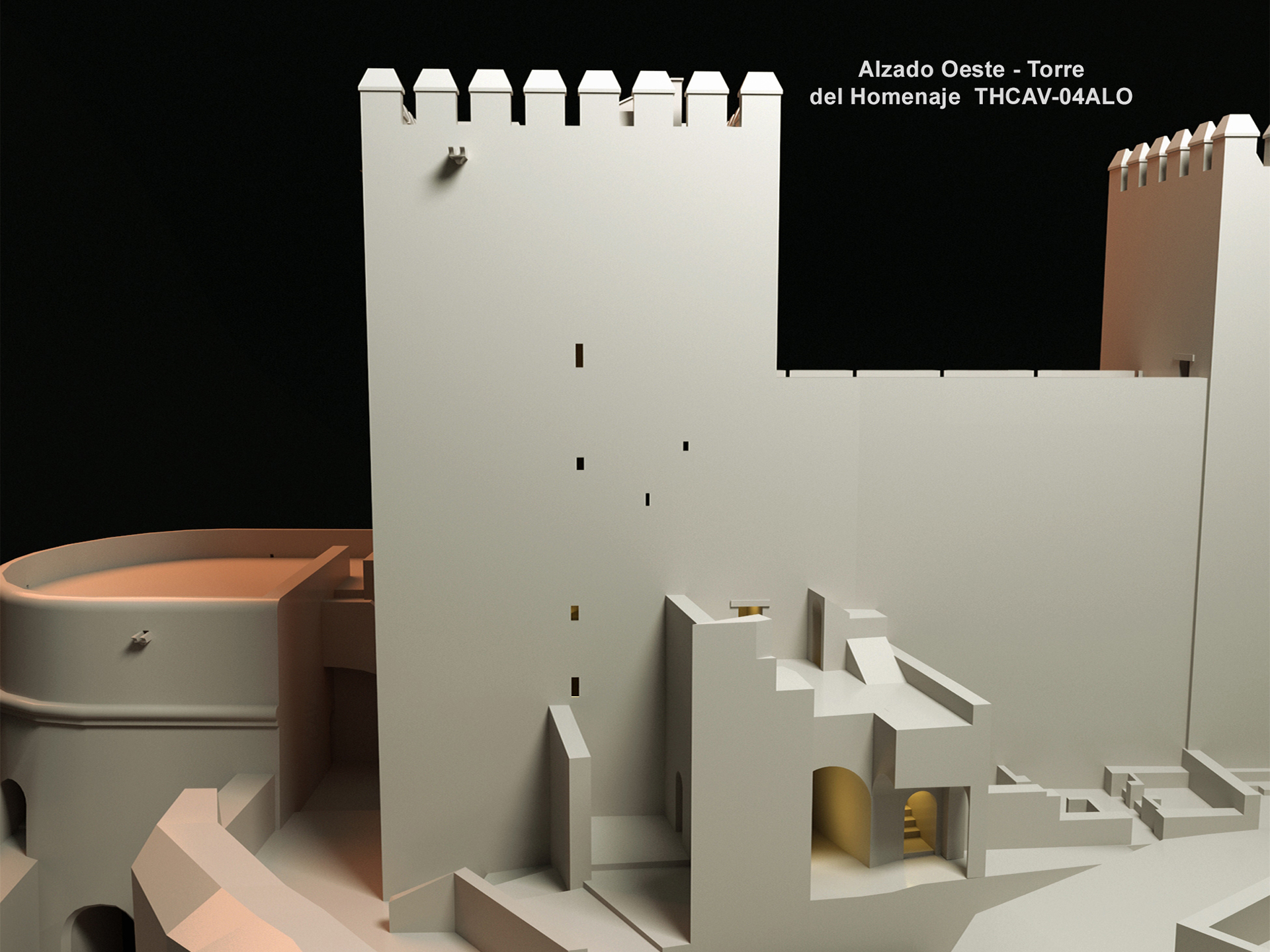

IL. 19. Adelaida Martín Martín, West elevation. The Homenaje, 2015. Rendering, 1950x1453 pixels

IL. 20. Adelaida Martín Martín, Projection of ceilings per level . The Homenaje, 2015. Rendering, 3657x3195 pixels